There's a famous myth that the tongue is the body's strongest muscle. It's not really true -- and not by any definition of strength. But that shouldn't make the tongue any less impressive. This muscular organ is vital for jump-starting the digestive process by guiding and molding food as well as perceiving its taste and texture, shaping the mouth to create speech and, of course, kissing. But what is this unusual muscle? And how does it move to perform its diverse responsibilities?

The tongue is composed of skeletal muscle fibers. Unlike the cardiac muscle or smooth muscle of the organs and digestive system, skeletal muscle can be willingly controlled. This allows for the tongue's mobility. The muscles that lace throughout the organ secure it to surrounding bones and create the floor of the oral cavity. Mucous membrane covers the skeletal muscle and protects the body from microbes and pathogens.

Advertisement

The tongue is an accessory digestive organ which, along with the cheeks, keeps food between the upper and lower teeth until it's sufficiently masticated, or chewed. The tongue is also a peripheral sense organ, one that helps perceive the sensation of taste and responds to pressure, heat and pain. The organ's flexibility allows for speech.

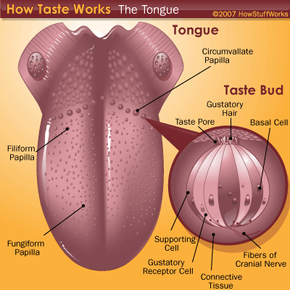

In this article, we'll learn about the anatomy of the tongue and its digestive, gustatory and lingual roles.