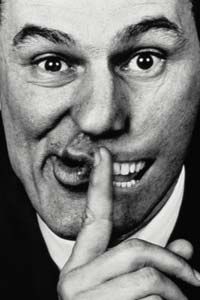

When you're young, there's one lesson that gets hammered into you more often than others: Tell the truth. Tell the truth, you're told, and everything will be OK. Then why does Mom call her boss claiming to be sick when she's not, and why does Dad say Mom's dress doesn't make her look fat? The lesson didn't stick for them when they were little, and it didn't stick with you or me, either.

Lying isn't a sign of moral depravity (except when it is). Lying is a sign of cognitive advancement. It requires a fertile and high-functioning brain to take something as simple as the truth and twist it, palming off the deception on someone else with the earnestness of a choirboy.

Advertisement

The problem with the truth is that it doesn't always serve our purposes, further our careers or keep us out of trouble. When you can take the route made of imagination, best-case scenarios and wish fulfillment, you'd be nuts not to take a deceitful stroll toward your goals, right?

Younger children believe that they're always being watched, and that Mom (or some other authority figure) knows all. For this reason, they're initially more inclined to tell the truth. As they get a little older, they begin experimenting with lies: The dog is blue, my shirt is made of copper, the cookie told me so. For the very young, lying is a series of cause-and-effect experiments. When does a lie work? What kind of lie? What is a believable lie? Is the jig ever up, or should I keep lying until the truth is just a vague memory for all parties?

Around age 2 or 3, children realize that they're not under constant observation by an all-knowing, all-seeing Eye of Truth. A typical 4-year-old stretches the truth once every two hours, while 6-year-olds will tell a whopper every 90 minutes [source: Bronson]. They're applying their earlier lie studies toward the general goals of all truth-stretchers: gaining advantage, staying out of trouble and "bigging" themselves up in the eyes of others. As children become older, they become more skilled at deception. And they never really stop. Continue reading to learn the truth, or something like it, about lying.

Advertisement