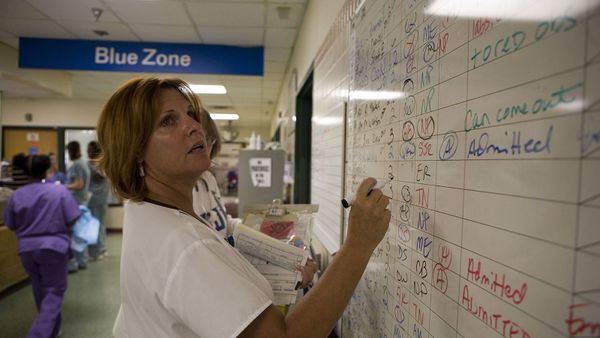

After eight years practicing family medicine at a traditional doctor's office in Boise, Idaho, Dr. Julie Gunther was burned out. She had 2,300 patients under her care, which meant that appointments were seven-minute rush jobs and new patients had a three-month wait to see her.

This wasn't why Gunther had become a doctor or what she had trained for decades to do. The pace took a toll on her physically and emotionally. She came home angry and tired, and her relationships suffered.

Advertisement

"I knew I had to do something different," Gunther says.

In 2013, she heard about a new health care business model called direct primary care (DPC). Instead of billing patients through insurance for each appointment and procedure — a bureaucratic nightmare that Gunther believes negatively impacts patient care — DPC doctors charge a flat monthly fee. No insurance, no copays. Patients pay in cash and can see their doctor as much as they want.

Now Gunther runs Spark MD, a small DPC clinic in Boise with a maximum of 600 patients. Adults pay $79 a month, kids pay $10 a month, and patients 90 years old and above are free.

A Spark MD monthly subscription includes same-day sick visits, comprehensive physical exams, common procedures like pap smears and wart removals, and more. Lab tests and X-rays are available for steeply reduced fees. And Gunther's in-house wholesale pharmacy sells generic meds at a fraction of the retail cost, even with insurance.

But most important for Gunther is that she can finally spend time with her patients, giving them the personal and comprehensive care they deserve. Appointments often run over an hour, and patients can reach her after-hours and on weekends directly on her cell phone. She calls it open-access scheduling.

"It's the gold standard for high-quality primary care," says Gunther. "It means that you have a profound capacity to meet people when they need you. If someone calls in right now, they can get in today. That fundamentally changes the entire structure of how you take care of people."

Advertisement