Before we had antibiotics, there were few choices when it came to treating infections: You could wait and see if the infection improved on its own, or you could cut the infection off of your body. It wasn't until 1928 that the very first antibiotic was discovered -- accidentally, at that -- when researcher Alexander Fleming came back to work after a weekend away from his lab and found a certain type of mold, Penicillium notatum, had halted the growth of Staphylococcus (staph -- a bacteria that can cause skin infections, pneumonia and some food-borne illness, among other infections) in his petri dishes. And not only did it kill Staphylococcus, it also worked when he tried it against other bacteria, including Streptococcus, Meningococcus and Diphtheria bacillus.

Antibiotics work against bacterial infections; many of us have used them to treat infections ranging from strep throat to bladder infections and many types of skin infections. But they won't do any good against a viral infection, including colds and most coughs, influenza or gastroenteritis (which is often referenced by the misnomer "stomach flu"). While all antibiotics will kill or stop the growth of bacteria, not all antibiotics are effective against the same bacteria, and not all antibiotics fight bacteria in the same way.

Advertisement

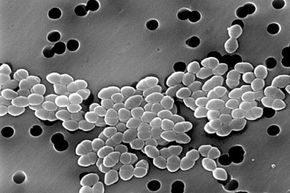

The type of antibiotic your doctor prescribes to treat your infection depends on the type of bacteria causing that infection. Most bacteria fall into two types: Gram-positive and Gram-negative. These classifications are based, basically, on the type of cell wall that the bacteria has. Gram-positive bacteria -- such as Streptococcus -- have thin, easily permeable, single-layered cell walls. Gram-negative bacteria -- such as E. coli -- have thicker, less penetrable, two-layer cell walls. For an antibiotic to successfully treat a bacterial infection, it needs to be able to penetrate either or both types of bacterial cell walls.

Let's get down and dirty with how antibiotics destroy bacteria.

Advertisement