"Show me where it hurts."

For all of its painful associations, it's a tender phrase, one we associate with parental love and the occasional doctor's visit. As children, we couldn't use fancy words to describe our scrapes, but we could point and wince, and somehow the medicine knew where we hurt.

Advertisement

Or so it seemed. In reality, painkillers are less magic bullet and more shotgun blast: They cruise through the bloodstream, mixing metaphors and sabotaging the machinery of pain wherever they find it. So, if your head happens to be splitting when you pop a pill for your aching back, you get a twofer.

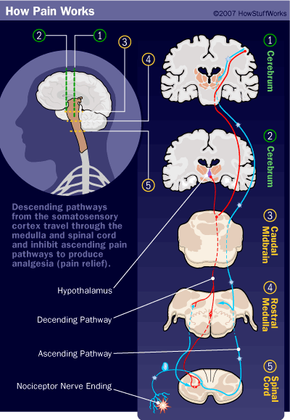

If you picture your body's nervous system like a series of Civil War telegraph wires, then you can imagine a series of dispatches coming into headquarters reporting damage from all over the country, which the president -- your brain -- experiences as pain. If you want to relieve the president's pain, you need to stop the sender, interfere with the wires or post a spy to intercept the messages. If you get really desperate, you can always knock the president unconscious.

Various pain meds adopt each of these approaches. Analgesics lessen pain without blocking nerve impulses, messing with sensory perception or altering consciousness. They come in many varieties, including anti-inflammatory drugs that reduce pain by shrinking inflammation. Analgesics also include COX inhibitors, which stop the signals, and opioids, which decrease the severity of pain signals in the brain and nervous system. When these just won't do, doctors turn to anesthetics, which just block all sensations, pain or otherwise, by knocking you out or numbing a particular area [sources: Encyclopaedia Britannica; Ricciotti and FitzGerald; Wood et al.].

So these treatments don't zero in on pain; rather, they wander along the transmission right-of-way, looking for pain-carrying messages and then blocking, destroying or intercepting them. To understand how this works, let's take a closer look at the physiology of pain.

Advertisement