Westend61/Getty Images

You may hear about babies or pets with hip dysplasia, but it can affect adults, especially young women.

People who've heard of hip dysplasia often think of it in connection with babies and dogs. One baby in 1,000 is born with hip dysplasia, but only 12 percent of those have unstable hips past the age of 2 months [source: Ramsey]. And hip dysplasia is common in dogs, particularly in large breeds. Hip dysplasia doesn't occur only in infants and pets, though. People, particularly women, can be diagnosed with and treated for hip dysplasia as adults.

Hip dysplasia is an abnormal condition affecting the hip socket, or acetabulum, and the thighbone, or femur. In someone with hip dysplasia, the hip socket is too shallow, or the femur is in the wrong place. Historically, many doctors have referred to hip dysplasia as congenital dysplasia of the hip (CDH). However, in the last decade or so, developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) has become the accepted term, since hip dysplasia can either exist from birth or develop in the first few weeks, months or years of life [source: Larson et al]. Eighty percent of all people with DDH are female [source: Ramsey].

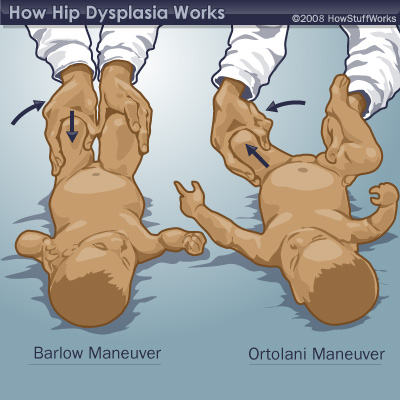

Doctors check for hip dysplasia in babies before sending them home from the hospital -- it's an easily treatable condition in newborns. But if hip dysplasia isn't detected and corrected at an early age, the health of the hip will deteriorate over time because of its misalignment. Depending on the severity of the situation, this could result in pain, osteoarthritis, difficulty walking or an inability to walk. It can also contribute to a marked deterioration in a person's basic quality of life.

How can a baby's development lead to a hip socket that's not deep enough, and what can doctors do to treat the issue? If someone discovers she has hip dysplasia as an adult, what are her options for treatment? You'll learn the answers to these and other questions in this article. We'll start with a look at the anatomy of the hip and how it changes in someone with hip dysplasia.

Advertisement