When the CDC announced in September 2006 that everyone between the ages of 13 and 64 should start getting tested for HIV as regularly as they get tested for, say, a normal heartbeat or high cholesterol, it created a bit of stir in the medical community. While most health experts applaud the recommendation on principle, the logistics of widespread, regular HIV testing for people not typically considered to be at risk may be problematic. Testing can be expensive, time-consuming (for patients, doctors and laboratories alike) and upsetting. And some people just cannot bear to be stuck with a needle.

At least on that last point, there's a viable solution: a recently FDA-approved rapid HIV test (one that doesn't have to be sent to a laboratory for processing) that can use blood, serum or oral fluids with equal accuracy. A simple swab of the mouth and gums is all that's required for the OraSure OraQuick Advance test, which is the only HIV test approved for oral use as of September 2006. Depending on who you ask, the oral test is either just as accurate or a partial percentage point less accurate than a blood-based test, with false positives being slightly more likely than false negatives.

Advertisement

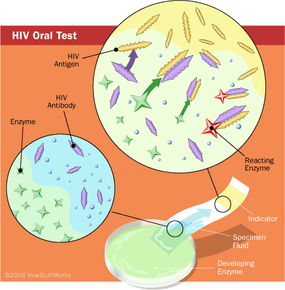

The OraSure test doesn't use saliva. It uses an fluid called oral mucosal transudate, which lives in the cheeks and gums. Aside from the fluid it uses for testing, the oral HIV test works just like the HIV blood tests -- it's testing for HIV antibodies, not the actual disease. When a person has HIV, his or her immune system produces antibodies in a futile attempt to kill the virus (see How Your Immune System Works to learn about the antibody response). So if a person has HIV, he also has HIV antibodies. And while an infected person's oral fluid contains hardly any of the HIV virus itself -- that's why kissing won't transmit the disease -- it contains plenty of HIV antibodies. The thing that makes antibodies a good substance to test for is that when the immune system produces antibodies in response to the proteins for a specific disease, which are called antigens, the antibodies bind to those antigens in an attempt to fight off the disease. If you add another protein, or enzyme, into the mix that reacts to the binding of antibody to antigen, you have yourself a good test for the disease. That's basically what the oral HIV test does.

The OraQuick Advance device holds a test strip. High up on the test strip, within the plastic casing, a substance with the makeup of HIV antigens has been applied. A patient places the end of the test strip in his or her mouth and swabs his cheeks and gums. The test administrator then places the end of the device in a vial that holds an enzyme solution that reacts to any antibody-antigen binding. As the oral fluid and the enzymes make their way up the test strip, they encounter the HIV-antigen substance. If there are HIV antibodies in the oral fluid, they start to bind to the antigens, and the enzyme reacts, causing a color change on the strip. This produces a line on the read-out portion of the device. This line indicates a reaction -- it is not considered to be a definite positive. As with all other HIV tests, OraQuick requires a repeat test before a patient is considered to be HIV positive. If no line appears at the site of the antigen substance, that's considered a negative result (no HIV antibodies present).

The oral HIV test takes about 20 minutes to produce results. The OraQuick device is not available over the counter and should not be used for home testing. For an oral HIV test, you should go to your doctor or to a clinic that provides the service. Following this test, you must still return to your doctor for a more specific one because HIV antibodies may not appear until three to six months after infection.

For more information on HIV testing and related topics, check out the links on the next page.

Advertisement