It was a disease like no other, in terms of worldwide scope. One hundred years ago, the Spanish influenza pandemic caused the deaths of at least 50 million people around the globe, although some experts think the death toll might have been as high as 100 million. Compare that with the last H1N1 flu pandemic of 2009, which killed an estimated 284,000 people, yet still managed to grip the world with fear. It's easy to see why some people would be skittish about the possibility of an event as huge as the 1918 one happening again. But now that we know so much more about how diseases are spread, how is this possible?

Paris-based science journalist Laura Spinney literally wrote the book on the 1918 pandemic (it's called "Pale Rider: The Spanish Flu of 1918 and How It Changed the World" and was excerpted in the Saturday Evening Post). "I think the thing to understand is that the experts consider 1918 to be very exceptional," she says, adding that of the last five flu pandemics, none were so deadly as 1918's. "It was in a league of its own."

Advertisement

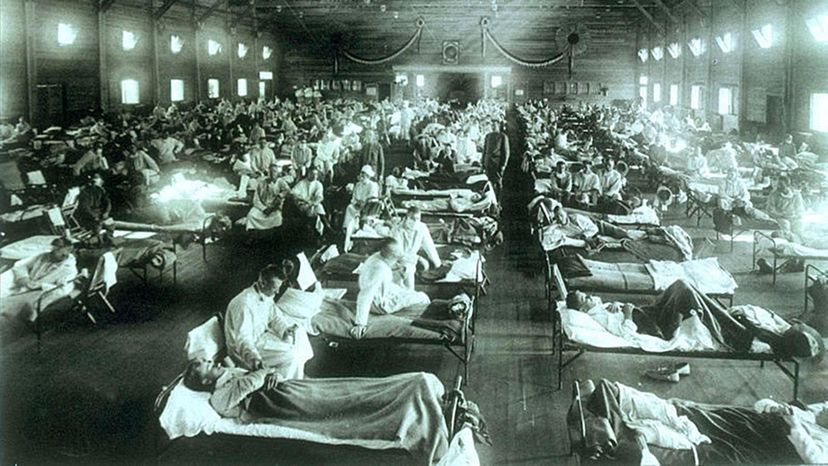

The 1918 flu was insidious and sneaky in nature, which helped it to sicken more than one-fifth of the world's population at the time. It would be the equivalent today of a disease sickening 1.5 billion people worldwide.

The first phase of the pandemic occurred in the spring of 1918 and caused few deaths. It roared back with a vengeance that fall, however. A less deadly, but still devastating third wave emerged again in the spring of 1919. The reason for the end of the pandemic is still a mystery. All told, Spanish flu would cause the deaths of more people than any other plague-like illness in history.

In the U.S., it was first detected in military camps. Although the disease's origins have been hotly debated (was it Europe, the U.S. or even China?) Spinney — and others — believe that Kansas was ground zero because the strain that caused Spanish flu in humans resembled one circulating in birds there at the time. The close quarters and massive troop movements of World War I helped to spread the disease around the world — and officials in various countries initially kept quiet about it to maintain public morale. In the end at least three times as many people died from Spanish flu as from all the conflicts associated with Word War I.

Th symptoms initially were those of classic flu — fever, sore throat, headaches — but later patients turned blue in the face, bled from noses and mouths and had trouble breathing. If their lungs got too congested with fluid, they couldn't breathe and died within hours or days.

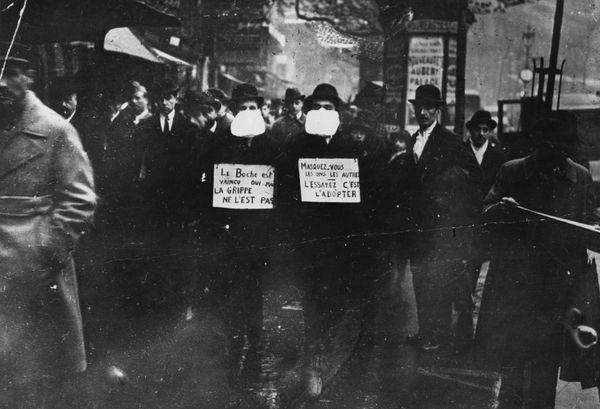

Back then, scientists had not yet discovered viruses, so there were no tests nor drugs to help treat the deadly disease. But the severity of the outbreak led to many ground-breaking innovations in public health that we've come to take for granted.

Advertisement