In 1698, on the coast of England, Henry Winstanley lit 50 candles at the top of his invention: the Eddystone Lighthouse, the first lighthouse to ever be built on rock. Five years later, in what has become known as the "Great Storm," the lighthouse collapsed and killed him while he was making repairs to the structure.

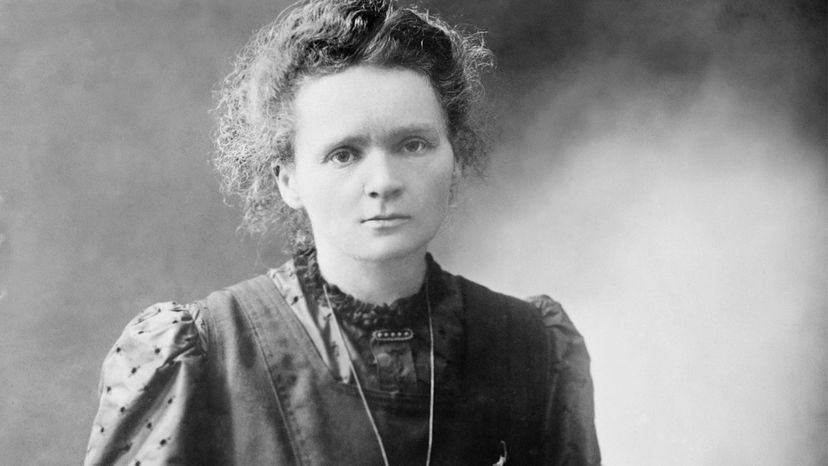

On July 4, 1934, two-time Nobel Prize winner Marie Curie died at the age of 66. The cause? Radiation poisoning from a life working with two of her discoveries: the highly radioactive materials of radium and polonium.

Advertisement

And in 1945, radiation would claim the life of another inventor: physicist Harry Daghlian, who was working on a plutonium bomb core of the Manhattan Project known as the "Demon Core." While stacking tungsten carbide bricks around the core, Daghlian accidentally dropped one that caused the assembly to go critical. While he immediately withdrew the brick and kept the device from exploding, he wasn't able to save his own life; he died of radiation poisoning a month later.

Although safety measures have improved dramatically today, the art of scientific exploration and invention has traditionally been risky business. In their quest to push back the boundaries of knowledge, inventors have been known to sacrifice whole lifetimes in service to their work, but some have literally given their lives to their inventions. Here we present five of them.