The U.S. has come a long way since the days of Reefer Madness. Thirty states — most recently, West Virginia — and the District of Columbia have approved marijuana for either medical or recreational purposes. And polls suggest more Americans than ever — 61 percent — want marijuana legalized nationwide.

While debate continues over marijuana's health benefits versus its risks, recent studies have placed cannabis squarely in the middle of the conversation over what has been called "the worst drug epidemic in U.S. history." And this time, some researchers say, marijuana might be a part of the solution.

Advertisement

As countless news reports have said, abuse of opioids — including prescription opioids, heroin and illegally manufactured fentanyl — is the leading cause of death in the United States. According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, an estimated 90 people die every day from opioid overdose, and 16,000 a year from prescription opioids alone.

Some observers link the epidemic to pharmaceuticals aggressively marketing highly addictive opioids since the 1990s, and doctors aggressively prescribing them to victims of chronic pain.

According to a 2014 study published in JAMA Internal Medicine "chronic noncancer pain is common in the United States, and the proportion of patients with noncancer pain who receive prescriptions for opioids has almost doubled over the past decade. In parallel to this increase in prescriptions, rates of opioid use disorders and overdose deaths have risen dramatically."

Methadone, oxycodone and hydrocodone are the most commonly overdosed prescription opioids, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

Further, a study released in the October 2017 edition of journal Health Affairs notes that as overdoses on prescription opioids have decreased since federal initiatives on prescriptions were put in place in 2010, overdoses on heroin and fentanyl have spiked. This strikes at the heart of the chronic-pain-and-opioids issue, signaling that addiction to opioids, not management of chronic pain, has become the central problem — i.e., making prescription opioids less available has only forced those addicted to seek other (often deadlier) resources.

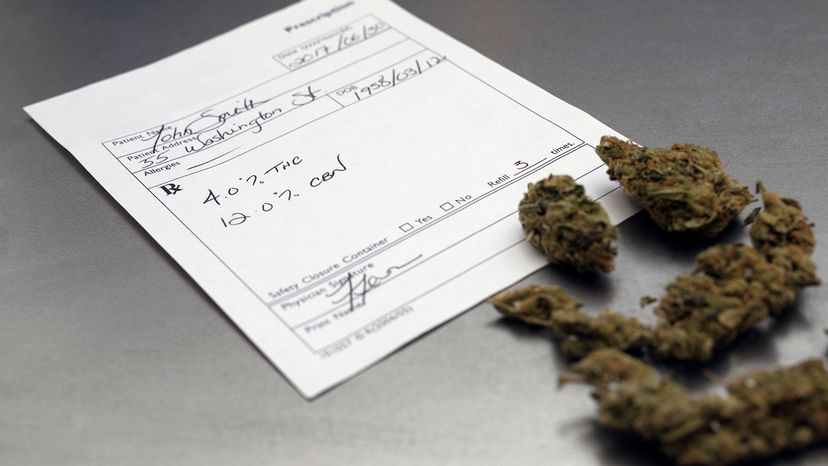

So, where does marijuana enter the picture? Well, in some cases, it doesn't — or, at least not legally. Marijuana is considered at the federal level a Schedule 1 drug, meaning, among other things, it's not accepted for medical use. On the state level, it is outlawed for medical and recreational purposes in 20 U.S. states. And in the 30 states that have approved it in one form or another, it's in the infancy of its introduction into medical and economic communities.

But several studies have shown that medical marijuana can do what opioids can do — manage chronic pain. Specifically, Nabiximols (a botanical extract of CBD and THC) has shown promise. And researchers from University of Pennsylvania did find that opiate-related deaths decreased by almost one-third in 13 states after medical marijuana was legalized.

"Marijuana, like any other medicine for pain, does not eliminate chronic pain, but it makes it more manageable," Dr. Beatriz Carlini, senior research scientist at University of Washington Alcohol and Drug Abuse Institute, says in an email. Carlini cites a 2017 report on cannabinoids from the National Academy of Medicine that collected results from several studies. The National Academy report concluded that "In adults with chronic pain, patients who were treated with cannabis or cannabinoids are more likely to experience a clinically significant reduction in pain symptoms."

Also, using medical marijuana instead of opioids virtually eliminates the possibility of overdose deaths, says Michael Patterson, CEO of U.S. Cannabis Pharmaceutical Research and Development, which baldly promotes its mission to "cultivate cannabusiness."

"Cannabis has never killed anybody in human history," Patterson says. "It's time we wake up and stop believing the fake news. Once you show people the facts about cannabis, it's hard for them to stay on their prohibition stance."

Cannabis does have potentially harmful side effects, Carlini maintains. Among other things, "its chronic and heavy use may result in 'cannabis use disorder,'" she says, "and early initiation of cannabis use may affect the developing brain. Also, in people genetically susceptible to psychosis, marijuana use can trigger schizophrenia and other psychotic states."

Still, victims of chronic pain in the U.S. are currently faced with choosing between 1) a prescription to opioids, which manage pain but are highly addictive and can lead to overdose and death, 2) limited access to legal or illegal medical marijuana, depending on where they live, and 3) over-the-counter pain relievers approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Carlini calls for an increase in access to medical marijuana, as well as education efforts targeting patients and healthcare about the potential for marijuana to treat chronic pain.

"In the long run, this can help," she says. "But recommending marijuana won't do much to prevent overdose deaths of those severely addicted to opioids, to help those already living [on] the streets, injecting heroin just to feel normal. At this point, their brains are already hijacked by opiates."

To help those with opioid addiction, Carlini recommends Medication Assisted Treatment (MAT), as well as access to Narcan, a prescription medicine that can block the effects of opioids and reverse an overdose.

Advertisement