Let's say you've picked up a ham and cheese sandwich for lunch. Before you even take a bite, your nose smells it and signals the brain, which sends word to the nerves controlling your mouth's salivary (spit) glands. Once the glands have their cue, they get busy secreting juices, making your mouth water. When you bite into the sandwich, the salivary glands get even more excited and secrete more saliva, making the food moister and easier to swallow.

Before the sandwich even leaves your mouth, an enzyme in your saliva called amylase begins to break down the carbohydrates in the bread. When you swallow, the sandwich pieces slide down your pharynx, also known as the throat. They then come to a fork in the road: One pathway is the esophagus, which leads to the stomach, and the other follows the trachea, which leads to the lungs. Of course, the correct path is through the esophagus, but sometimes food can take a careless detour. So when we say something went down the "wrong pipe," it means it went through the trachea, usually because you were breathing or laughing when you swallowed. Not to worry, this rarely happens -- the act of swallowing closes the epiglottis, a flexible flap over the trachea. So the sandwich pieces will normally slide into the esophagus through the upper esophageal sphincter, a ring-shaped muscle that opens only when food is swallowed.

Once the sandwich is in the esophagus, involuntary muscle contractions -- or peristalses -- push it toward the stomach. At the end of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter lets the food into the stomach. It opens and then quickly closes to keep the food from escaping back into the esophagus. Ever had heartburn? This occurs when this sphincter isn't working properly and stomach acid manages to splash into the esophagus. If this happens chronically, you might have Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease, or GERD.

In the stomach, the food begins its preparation for the small intestine. Glands in the stomach secrete acid, enzymes and a mucous that coats and protects the stomach from its own acids and prevents ulcers. The stomach's smooth muscles contract about every 20 seconds, stirring up the acid and enzymes and turning your sandwich into a liquefied blob (chyme). But some foods just can't be reduced to chyme and remain a pasty, solid substance that is released into the small intestine in a process that takes more than an hour. Your liquefied sandwich, however, can be out of the stomach in a mere 20 minutes [source: Gastro.net].

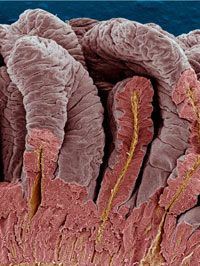

Next stop: the small intestine.