Twenty-five-year-old Stan Larkin left the University of Michigan Frankel Cardiovascular Center with a heart transplant a few weeks ago. But what made this so remarkable is that for 555 days before the surgery, he'd lived without a heart of his own. He relied instead on an artificial heart that was kept going by a 13.5-pound (6-kilogram) Freedom portable driver, or power supply, nestled in a backpack.

As a teenager, Larkin was diagnosed with arrhythmogenic right ventricular dysplasia, or ARVD, a type of heart disease that can strike healthy people without warning. It tends to be hereditary and often strikes athletes. Indeed, Larkin was diagnosed after collapsing at a basketball game.

Advertisement

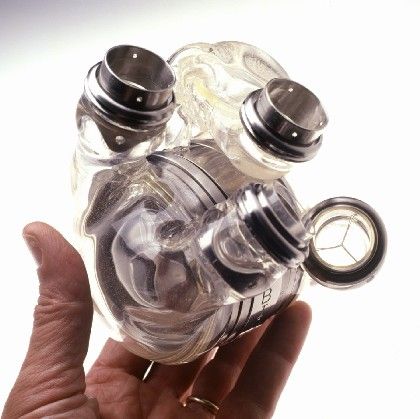

As both sides of his heart began failing, Larkin was put on the waiting list for a heart transplant. His diseased heart was also removed, and he was given a total artificial heart in December 2014. With this type of heart, there are two tubes that exit through the stomach to a machine (driver) that delivers compressed air into the heart's ventricles. This allows blood to flow through the body.

Before the portable driver was developed, the only option was a hospital model that weighed 418 pounds (190 kilograms) and forced the patient to remain in hospital indefinitely while waiting for a heart transplant. Larkin was the first patient in Michigan to be discharged with the portable machine.

The first U.S. patient to ever be discharged with a portable device got one in 2010. The Freedom driver was approved by the U.S Food and Drug Administration in 2014, and its manufacturer, SynCardia, says that more than 150 patients worldwide use it outside of the hospital.

Doctors weren't sure how Larkin would fare with this artificial heart out in the real world, wearing it 24 hours a day. But he exceeded their expectations, even playing pickup basketball with it.

"He really thrived on the device," Larkin's surgeon Jonathan Haft, M.D. said in a press release. "This wasn't made for pick-up basketball ... Stan pushed the envelope with this technology."

In May 2016, Larkin was able to give up his artificial heart when he finally received his transplant. Two weeks later, he said in a press release: "I feel like I could take a jog as we speak. I want to thank the donor who gave themselves for me. I'd like to meet their family one day. Hopefully they'd want to meet me."

Advertisement