On a January night in 1879, as a squad of police officers stood guard to keep them from escaping, a dozen prisoners were marched to a dock in Honolulu, Hawaii, and put aboard a steamer called the SS Mokolii. The ship set sail, and the next morning it arrived at the destination -- Kalaupapa Peninsula, an isolated spot on the north shore of Molokai. The prisoners were ordered into boats and rowed themselves to the rocky, desolate shoreline. Other officials were waiting to record their names and introduce them to their new home, from which they would never be allowed to leave [source: NPS].

Though these prisoners were considered so dangerous that they had to be kept far away from the rest of human civilization, they had committed no crimes. Instead, they were patients afflicted with leprosy, also known as Hansen's disease, a bacterial illness that causes skin sores, nerve damage and muscle weakness that, if untreated, gets progressively worse over time. Today, thanks to modern science, doctors know that leprosy is not particularly contagious, and that it can readily be treated with antibiotics. But for much of history, leprosy was a terrifying, mysterious menace, feared because of its potential to ruin faces and cause fingers and toes to die or shorten [source: NIH].

Advertisement

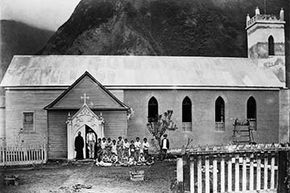

As a result, countless people all over the world with leprosy have been shunned, ostracized and sometimes forcibly banished from society altogether. They were sent to live in isolated communities known as leper colonies, or leprosaria, where they spent their lives suffering out of view of the uninfected people who so feared them.

Fortunately, though leprosy has not completely vanished, today people with the disease are seldom treated in such an inhumane fashion. However, leprosaria still exist in a few parts of the developing world. Why were people with this particular disease banished from society and why does it still persist?

Advertisement