Malaria. Not a good thing, right? And when a patient sought treatment for his high fever back in 1976, that's what everyone assumed he had. He was, after all, living in the country then-known as Zaire, a place well-known for high rates of malaria infections. So a nurse treated him for it with an injection of quinine and sent him on his way. Since she was low on supplies, she kept the needle she used to inject Mabalo for other patients.

Less than a month later, the patient died. As was customary in his region, his female friends and relatives performed a ritual burial procedure on his remains, removing all food and waste from his body with their bare hands.

Advertisement

Fast-forward a few weeks: Eighteen of the friends and family who had helped with this ritual had also died, and the hospital that had used the dirty needle was flooded with patients showing similar symptoms.

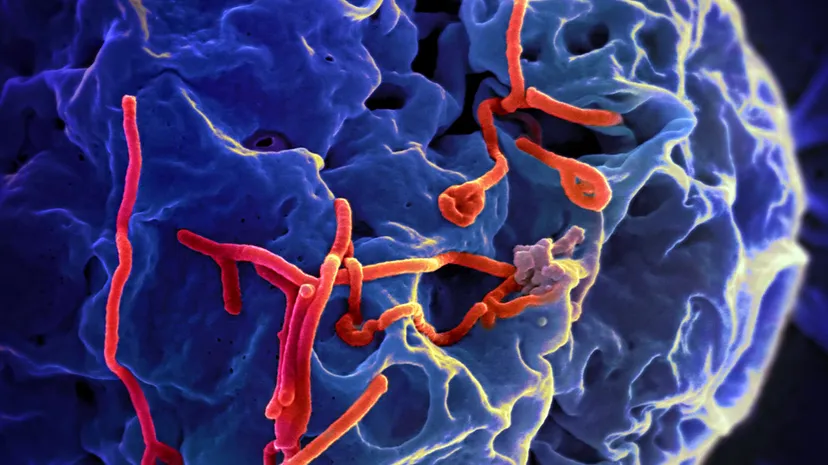

Malaria is bad, but not this bad. Doctors and scientists studying patient samples from this outbreak and a similar one occurring simultaneously in Sudan quickly realized they were dealing with something never before seen — the Ebola virus. All in all, 91 percent of the 358 people infected in Zaire died, and 53 percent of the 284 infected in Sudan succumbed to the disease [source: Smith].

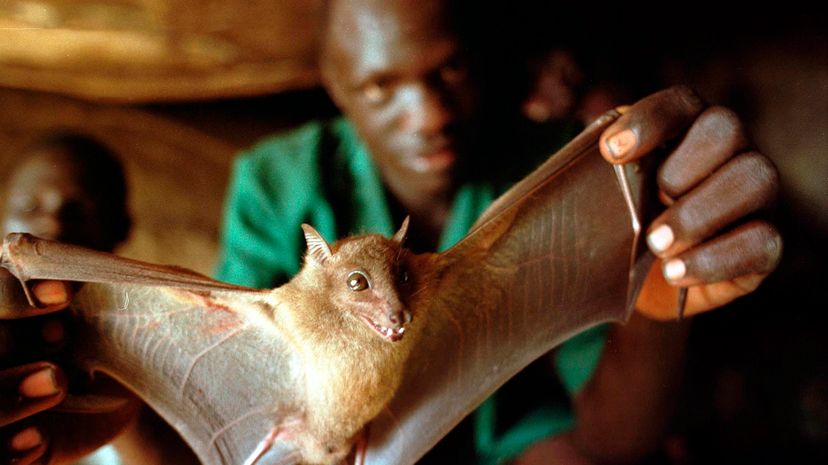

Since 1976, the disease has popped up more than 20 times, mostly in Africa. And it's not showing signs of stopping. If anything, it's getting worse, spreading beyond its main hub of central Africa as far as Europe and the United States as of November 2014. More recently, in May 2018, an Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo spread to Mbandaka, a densely populated city of 1.2 million, where authorities worried that it would be difficult to contain [source: McKirdy and Senthilingam].

Just how scary is Ebola? The number of fatalities speak to that. But there's also the ruthless efficiency with which this virus can kill — as quickly as within six days of showing symptoms. The latter include fever and achiness to start, leading to rash, bloody diarrhea, vomiting, and in many cases, massive internal and external bleeding.

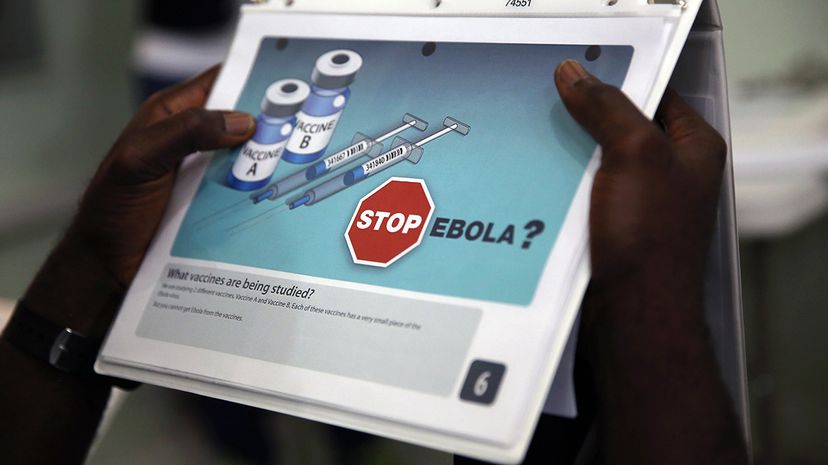

Decades after the discovery of Ebola, scientists are still probing its mysteries. But an experimental vaccine, which was 100 percent effective in human trials in Guinea in 2016 and was deployed on a large scale for the first time in May 2018 against an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, might prove to be the way to defeat the dreaded disease [source: Maron].

Advertisement