As we've seen in movies like "Contagion" or "Outbreak," infectious diseases can be terrifying. They kill people, spread like wildfire, cause mass chaos and collapse entire governments. Even though these movies are fictional, they're not that far from the truth. So why on Earth would scientists and researchers keep a stash of every contagious disease out there in their labs?

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) stores samples of viruses and diseases to keep us safe. That might sound counterintuitive, but the only way to learn about disease and control outbreaks is to know your enemy. When an outbreak occurs, the first step in halting it is to identify, or diagnose, it. Once a disease is diagnosed, scientists and medical professionals can take steps to control it. During the control phase, researchers can work on the pathogen to find a way to treat it and later, with skill and luck, prevent it.

Advertisement

Researchers also keep samples of contagious disease for surveillance. The World Health Organization (WHO) works internationally to keep tabs on diseases affecting public health. This global surveillance system, through which participating countries report communicable diseases, allows WHO to identify emerging diseases or learn of new outbreaks of existing diseases. This allows the control mode to go into effect that much faster.

One of the most developed worldwide virus partnerships is influenza surveillance. Because the influenza virus mutates into different strains, it can become vaccine resistant. Each year, by analyzing past and developing data coming in about the flu virus, researchers decide which strains will be included in the annual flu vaccine. So, every year, the flu shot adapts, just as the virus itself adapts.

Sometimes these samples can even help scientists "go back in time" and solve the mystery of unexplained deaths. For example, the bacterium Legionella pneumophila caused a large outbreak of Legionnaire's disease in 1976. Once researchers isolated the bacterium, they looked at tissue samples that resembled the current outbreak and found there had been unidentified outbreaks in 1956 and 1947 [source: CDC].

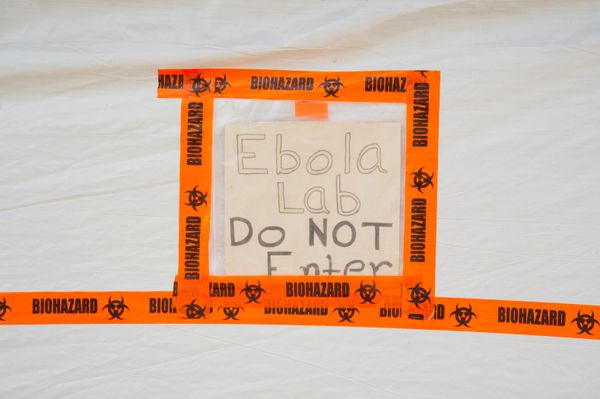

Whenever a local hospital or government agency becomes aware of an outbreak of infectious disease, or if a patient presents with symptoms never seen before, they notify the CDC and send in samples for identification. Local labs and professionals package and ship samples in accordance with CDC-approved guidelines to ensure safety. The guidelines include using trained lab workers, having redundant controls and individually tailored safeguards for each lab in place, and being subjected to unannounced safety inspections [source: CDC].

Unfortunately, accidents still happen.

Advertisement