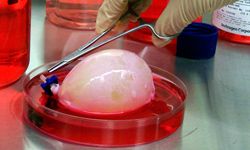

We may gripe and groan when our car breaks down, but the fact of the matter is, a car is easy and cheap to fix when you compare it to the human body. Your mechanic has an array of spare parts that fit the vehicle, and if what the car needs isn't in stock, it can be ordered. Not so with the human body. Our parts give out at random times, and ordering a spare heart or brain isn't so simple. Hundreds of thousands of people have died while waiting for transplant organs, while countless more have made do with replacement parts that neither look nor function like the real deal. But now, thanks to years of research, scientists are amassing a "body shop" of sorts for humans; instead of mufflers or tires, these experts deal in bladders, bones and breasts. As we travel this highway of life, our bodily blowouts and flat tires can be fixed, and in this article, we'll examine 10 of the body parts that can be rebuilt and replaced.

Advertisement