In almost every home, there's a junk drawer full of things we don't really need or use. Inside the drawer are buttons to long-gone items of clothing, washrags that started life as full-fledged towels, and rings of keys that unlock an assortment of past cars and houses. We don't really need the contents of these junk drawers anymore, but hey, you never know, right? Dad's old eyeglasses from the 1970s might make the perfect Halloween costume accessory someday.

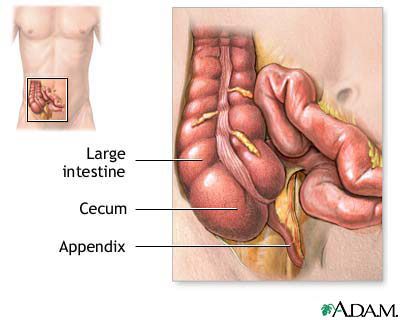

The human body has something akin to its own junk drawer. You can think of organs like the brain and the heart as belonging to your silverware drawer or the cupboard where you keep your plates -- they're useful items you need every day. But the body's junk drawer is full of vestigial organs, or souvenirs of our evolutionary past. We don't use these items for their original purpose anymore, and these parts are stunted mementos of that original function.

Advertisement

How do we know what each organ's original purpose was supposed to be? For that, we turn to Charles Darwin. While he wasn't the first person to identify bodily structures that seemed to serve no purpose, he did propose why we have them. His concept of common descent, a tenet of evolutionary theory, holds that all organisms started with a common ancestor but diverged and changed as certain traits proved more favorable and necessary for survival. In Darwin's 1871 book "The Descent of Man," he identified about a dozen of man's anatomical features he believed to be useless because we don't use them in the same way that other creatures do. This, to Darwin, was proof that we had evolved from our primitive ancestors.

By 1893, anatomist Robert Wiedersheim had built the list of vestigial organs to include almost 90 parts [source: Spinney]. But as with junk drawers, one man's trash is another man's treasure, and people started arguing about what was on the list. Some of Wiedersheim's vestiges were shown to have an important function, indicating that these body parts weren't just reappearing by accident. Others take umbrage with Darwin's theory entirely, arguing that everything in the body has a purpose assigned by a creator, and just because we don't know the function doesn't mean it doesn't exist.

Advertisement