Fingerprints follow us our entire lives. Each little smudge singles us out as distinct individuals among billions of other human beings -- or at least that's what we've always been told.

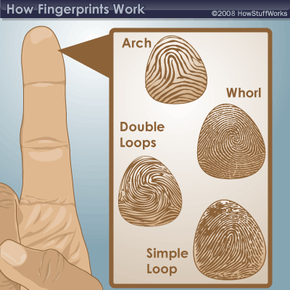

Even identical twins boast different fingerprints. One crafty Olsen sibling couldn't leave the other's prints on a murder weapon, because all of those unique loops, ridges, whorls and arches were writ inside the womb by pressure on the twins' developing skin.

Advertisement

See, the outer epidermis and the inner subcutaneous tissue sandwich the dermal cell layer between them like a slice of cheese between two slabs of bread. As the pressure builds, this "slice of cheese" compresses and buckles, erupting in random surface patterns [source: Ray].

In fact, the chances of two people possessing an identical fingerprint are slim, though not quite impossible. According to 19th-century polymath Sir Francis Galton, those odds were 1 in 64 billion [source: Stigler]. But according to fingerprinting expert Professor Edward Imwinkelried, since the world population now exceeds 6.4 billion and most of us possess 10 dainty digits, we have more than 64 billion prints out there to bump up the odds of "sharing" a single print with a stranger. That's one reason why multiple fingerprints are important for positive identification; the probability of people having three fingerprints in common are on the order of 100 quadrillion to 1, says Imwinkelried. It's also why he and other experts press for fingerprinting reform and greater reliance on DNA evidence.

According to statistician Stephen M. Stigler, 20th-century reliance on fingerprinting had less to do with science and reliability and more to do with courtroom drama and a fortunate lack of pattern repetition in prints. It's hardly a perfect method. Since 1995, evaluations of fingerprinting labs by Collaborative Testing Services have discovered fingerprinting error rates ranging from 3 percent to 20 percent [source: Arpin].

Advertisement