"Saliva's roles cover all the functions of the mouth you can think of," Carpenter says, "including taste, chew, swallow, smell (aerosol generation), maintenance of mucosal tissue, lubrication of fats, maintenance of oral microbiome, speech, etc."

That's a mouthful, so let's break it down and discuss some of the important functions saliva plays in our bodies.

Saliva Helps You Taste Food

Your tastebuds get all the credit for allowing you to taste food. But they'd be practically worthless if not for saliva, Carpenter says. It's difficult for our tastebuds, which lie in deep channels across our tongue, to assess dry, lumpy, aroma compounds without a dose of saliva. Skeptical? Dab your tongue dry, then place one lump each of rock salt and rock sugar on your tongue. It'll be next to impossible to differentiate between the two lumps without allowing a wave of saliva to wash over them.

Saliva also contains digestive enzymes that help boost a chemical reaction that signals to the brain that what we are eating is, in fact, nutritious and safe to swallow.

Jianshe Chen, a food scientist at Zhejiang Gongshang University in Hangzhou, China, came up with the term “food oral processing,” which he wrote about in a paper titled "Current Perspectives on Food Oral Processing," published in the Annual Review of Food Science and Technology in March 2022. He explained that we only perceive the flavor of foods if they can reach the taste buds. To get there, food molecules must pass through and be coated with a thin layer of saliva. We aren't actually tasting the food, but the mixture of the food and the saliva. But the composition and the rate of flow of saliva is different for every person, so scientists don't know the exact science of how it affects food.

Interestingly, researchers have found that people with different salivary flow rates or more mucins in their saliva may have different flavor experiences from the same foods. For example, in one study detailed in the journal ScienceDirect in December 2019, scientists measured saliva levels in participants who agreed to evaluate the taste of wine to which fruity-flavored esters had been added. Those who produced more saliva tended to score the flavors as more intense. Researchers surmised that these participants swallowed more often, which forced more aromas into their nasal passages resulting in a more intense tasting experience. Which brings us to saliva and the nose.

Saliva Helps You Smell Food

Saliva can also affect the aroma of the food you eat, Carpenter says, which is responsible for the vast majority of your perception of flavor. As you chew, some flavor molecules dissolve in the saliva. Those that don't can waft into the nasal cavity and be sensed by the receptors there.

Saliva Prevents You From Choking on Your Food

Saliva plays another important role when we eat. As we chew, saliva joins in and (thanks in part to those mucins in our saliva) turns the dry, crumbly food bits into soft, cohesive lumps. These "bolus" hunks are better able to slide down our esophagus and continue their way through our digestive tract without us choking on them. It also helps protects our esophagus from getting damaged by any rough-edged food particles.

Saliva Helps You Digest Food

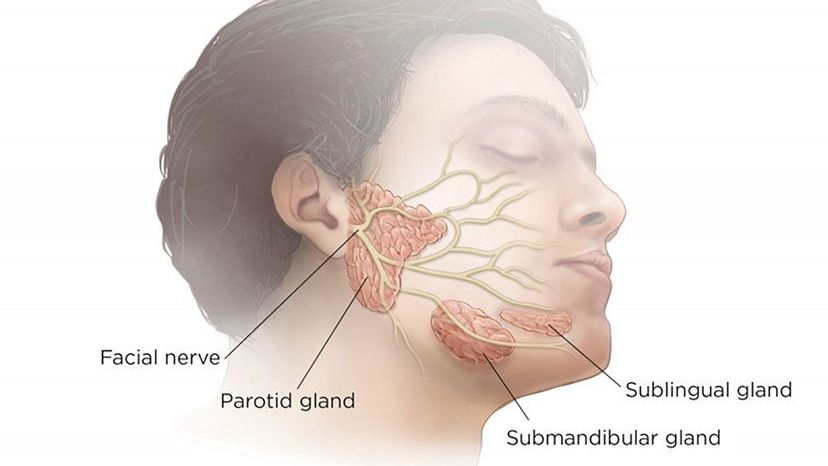

Remember that smaller cluster of salivary glands in the upper digestive tract and esophagus? They produce a type of saliva containing digestive enzymes. One is called salivary amylase, which breaks down starch into sugar so your body can absorb it more easily. The other, called lingual lipase, helps break down fats. These enzymes prepare the food you've swallowed for the stomach.

Saliva Protects Your Teeth

Your saliva is also saturated with calcium and phosphate ions that help protect the enamel surface of your teeth. Without this concentration in your saliva, the enamel on your teeth would start to erode. This explains "nursing bottle syndrome," a condition in infants who suck on bottles filled for prolonged periods of time. The nipple of the bottle can prevent saliva from washing away the sugars from the top incisors, resulting in early childhood cavities. Saliva also protects your teeth from tooth decay by helping dilute dietary carbohydrates and neutralizing the acids from plaque.

Saliva Helps You Speak

You've probably seen speakers with a glass of water at the podium to sip on in case their mouth becomes dry. That's because it's difficult to speak with a dry mouth. Water can help, but having an adequate amount of saliva in the mouth lubricates the oral tissues, making it easier to talk smoothly.