In the grueling sport of rowing, each boat typically has a designated coxswain. This pint-sized leader steers the shell, generally by yelling instructions at the poor slobs rowing it. His job is to get the crew rowing in unison to keep the boat on course and swiftly moving ahead.

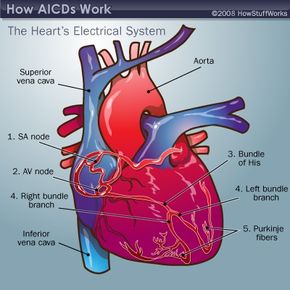

Your heart works much the same way. Your natural pacemaker, the sinoatrial or SA node, sends out an electrical signal that guides the rest of the heart tissue. For example, when you nap, you need very little oxygen, so your pacemaker sets a slower pace and enforces it with a slower electrical signal.

Advertisement

Heart disease, especially coronary artery disease, can damage your heart and its ability to send a signal. This damage can make the heart's electrical system go haywire, making it beat too fast or too slow. Sometimes other parts of the heart start calling out their own signals, and before long, different rowers are rowing to their own rhythm, drowning out the coxswain, or SA node.

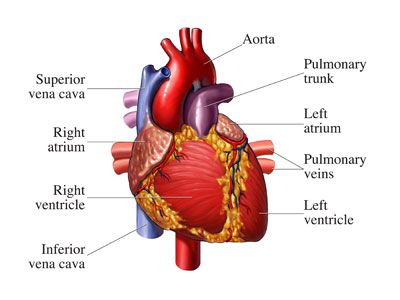

There's a name for this kind of confusion. It's called fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation, a fluttering that happens in the heart's upper chambers, is common and doesn't always require treatment. Think of it as two people in the boat who aren't coordinated with the other six rowers. The boat is moving. It's just not efficient.

But ventricular fibrillation, or when all the rowers are spastically splashing around and the boat isn't moving, is deadly. Why? Because when the cells produce different electrical signals, they don't work as a team to make the heart beat. Instead, the heart just quivers.

To force these chaotic heart cells into acting once more like a well-rowed boat, they sometimes have to be jolted into compliance. This can be done using hand-held paddles, or external defibrillators, that send a giant jolt through your body to get the heart cells back on the same rhythm. You've probably seen some version of a defibrillator in hospitals or maybe on "ER."

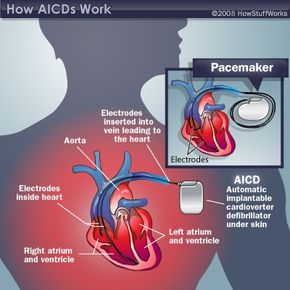

Your survival once depended on being near one of these defibrillators when your heart suddenly started acting like our dysfunctional boat. Then, in 1980, researchers developed a device that knew when to shock the daylights out of you, and it produced that shock from inside your own body. It's called an automatic implantable cardioverter defibrillator (AICD).

But before we talk about these amazing devices, let's learn about the heart's electrical system.

Advertisement