Don't call a shy person an introvert. Both extroverts and introverts can be shy. Introverts aren't necessarily quiet and sensitive, either, nor are they people-haters.

What characterizes introverts — and how their brains function differently than those of extroverts — dominated a recent episode of the podcast Part-Time Genius, co-hosted by Will Pearson and Mangesh Hattikudur.

Advertisement

The pair says that one-third to one-half of all people are introverts, a term coined by famed psychiatrist Carl Jung in 1921 (along with the term "extrovert"). While introverts tend to be not as well-received in Western society, which favors extroversion, both personality types have their pros and cons. They're merely different ways of experiencing and processing the world. In addition, "no one is really a hundred percent introverted or a hundred percent extroverted," says Pearson. " ... We're all really more of a mix of both personality types ... most of us lean harder one way than another."

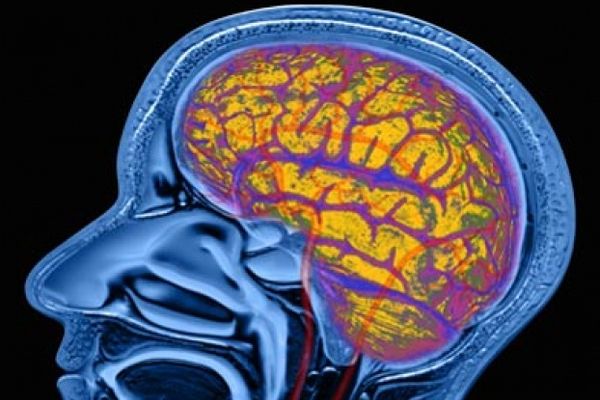

Introverts' brains work differently than those of extroverts. Introverts' brains are more sensitive to dopamine, a neurotransmitter that makes us feel good when we act quickly and take risks. This means they don't need much of it to become energized, and too much will be overstimulating; hence, introverts' preference for being alone or with a small group of people.

In addition, introverts' brains take in stimuli via the long acetylcholine pathway, a lengthy corridor (named after the neurotransmitter acetylcholine) that passes through different parts of the brain. The practical ramifications of such a lengthy journey mean that introverts are more likely to notice small details and errors, overthink things, and take a while to process and react to information.

Extroverts, in contrast, have a higher tolerance for dopamine, so they need more stimulation to feel energized and recharged. Thus, they enjoy busy situations and being surrounded by a large crowd of people. Their brains also receive stimuli quickly, allowing them to respond and react to various environments easily and rapidly.

These biological brain differences mean that introverts tend to be good listeners, avoid small talk, enjoy solitude and make fewer social gaffes because they think things through before speaking. They also can read people better, enjoy problem-solving and are less impulsive than extroverts, who tend to be risk-takers and are more likely to land in the hospital or in jail. But introversion has its downsides; introverts report feeling more loneliness and lower self-esteem than extroverts.

Pearson and Hattikudur say there's also a third recognized personality type: the ambivert. Nearly 40 percent of people are ambiverts, or someone who is part introvert and part extrovert.

Whether you're an introvert, extrovert or ambivert doesn't really matter, though. If you know which personality you tend to favor, you can work to its strengths. The most important thing is to be true to your temperament.

Advertisement