As far as biologists can tell, organisms on this planet have one job: to make more of ourselves before we die. The behaviors that go along with that — finding food, selecting mates, figuring out how to not die today — are all just ways we all support this one biological imperative.

But from there, things get complicated. It's pretty clear, for instance, why a cheetah would have evolved lightning speed. But why would a panda, who at one point evolved the gut of a carnivore, sit around eating bamboo all day? And it's fairly obvious how living in cooperative social groups has helped humans claw their way to the top of the pile, but a new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences looks at why we evolved one human behavior — feeling shame — that, at first glance, seems to do us more harm than than good.

Advertisement

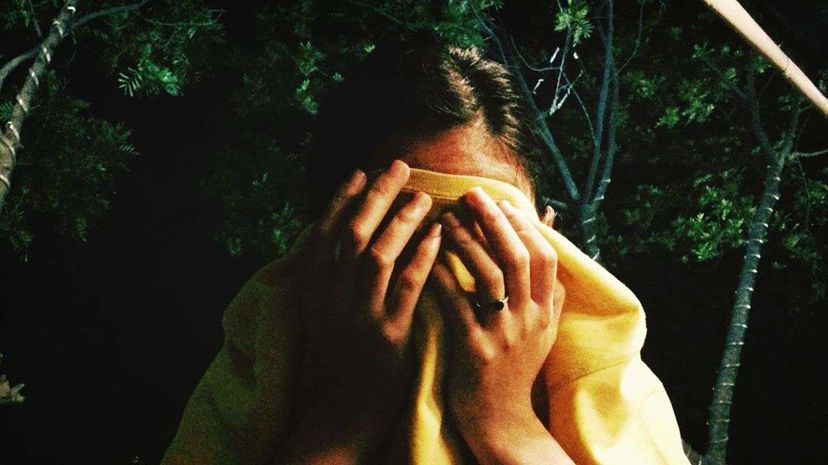

Shame doesn't make intuitive sense. It causes pain — a feeling usually reserved for helping us avoid damaging our physical body tissue — and often makes us act against our own best interests. Shame is an emotion responsible for the lies we tell, the paranoia and depression we feel, and can sometimes lead to dramatically self-damaging behavior.

But researchers at University of California Santa Barbara claim to have discovered an evolutionary root of human shame, and argue that it's necessary for the complex navigation required by living in a tight-knit community.

"Our human ancestors in the African savanna lived in a world without nation states, a police force, supermarkets, social security or savings accounts," says study lead author Dr. Daniel Sznycer, of the UC Santa Barbara's Center for Evolutionary Psychology. "Because of this, your reputation was even more important 100,000 years ago than it is today."

In order to be treated well, others in your community had to value you enough to protect you, share food with you, and help take care of your children. If they found out you were diseased, physically weak, stealing stuff, acting sexually out of the mainstream, etc., they might not deem you worthy of their help — they would "devalue" you.

"There would have been incentives for our ancestors to behave well — to not steal, for instance," says Sznycer. "And if we did steal, we'd want to prevent the leakage of that negative information. Shame makes people do things to avoid being devalued: hide things, destroy incriminating evidence, blame others."

The researchers found that shame works similarly across different cultures, too. In their study, they created 24 fictional scenarios about behaviors that evolutionary psychologists would expect to lead to devaluation and shame, ranging from stinginess to infidelity to stealing. Turns out, after posing these questions to 900 participants in India, Israel and the United States, they found that no matter who the audience was, everybody basically agreed about the level of devaluation they would feel about the perpetrator in the scenario, and the level of shame they'd feel if the they were the wrongdoer in the scenario.

"This stands in contrast to classical anthropological theories that say that meanings across cultures are not necessarily translatable," says Sznycer. "That model says that shame in the East and in the West are very different because people's conceptions of self are different. But if that were the case, you wouldn't expect the values of people to be so highly synchronised across cultures."

Shame feels so terrible as to seem maladaptive — why would something so ugly and even crippling have a function? According to Sznycer, the thing that feels bad is also protecting us.

"People who can't feel physical pain often die young because they don't have a mechanism to tell them when their tissue is being damaged," says Sznycer. "Shame is the same as physical pain — it protects us from social devaluation."

Advertisement