More than 25 percent of seniors over the age of 65 don't have a single tooth left [source: National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research]. Accidents, genetics and poor oral hygiene can also contribute to tooth loss in younger individuals. Once teeth are lost, humans are stuck with artificial replacements like dentures and implants, which may improve the appearance of the smile, but pale in comparison to natural teeth. While humans can't currently regrow teeth, scientists are making impressive gains in the field of tooth regeneration, often taking clues from other species – like alligators and puffer fish – which are able to easily regrow lost teeth.

The mighty alligator has a powerful bite, one he's able to regenerate by replacing lost teeth as many as 50 times over the course of his lifetime [source: Nuwer]. The tiny puffer fish shares a similar skill, creating new bands of dentine to replace his tooth-like beak if it becomes worn or damaged [source: The University of Sheffield]. By studying the molecular details of how these animals regrow teeth, scientists hope they can engineer stem cells to allow humans to perform the same feat. Keep in mind that these are not the stem cells you might associate with a fetus. They are the natural stem cells that already exist inside of your teeth.

Advertisement

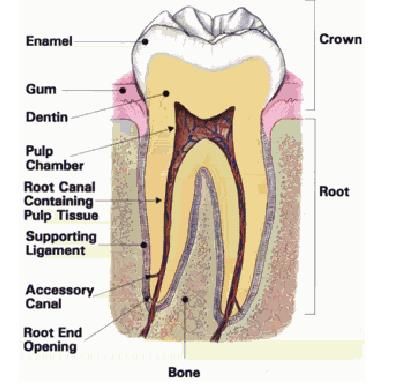

One group of researchers drilled holes in the teeth of rats, then directed low-level lasers into these holes. By exposing the pulp within the tooth to the pulses of light, scientists were able to program the stem cells within the pulp to rebuild lost dentine, thereby regenerating the tooth. If this research can be replicated in humans, it may serve as the first non-invasive way to repair teeth, allowing people to regenerate their smile without extensive dental work [source: Arany et al].

A separate study developed hydrogels, made from peptides, proteins and drugs, which they injected into the pulp beneath teeth. These hydrogels are designed to encourage stem cells to bring teeth back to life, eliminating the need for painful root canals. Even better, the hydrogel dissolves after the tooth is regenerated, leaving nothing behind that could harm the body or interfere with normal oral health [source: Williams].

While these methods are still in the experimental stage, they offer powerful potential for the future of dentistry. For now, steer clear of alligators, no matter how friendly their smiles may appear.

Advertisement