Most women are well-aware that irregular periods can be a real pain. But beyond just being annoying, irregular periods might come with a more serious worry: that erratic cycles are linked to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). And it wouldn't be entirely unlikely: As many as one in 10 women between the ages of 15 and 44 have the disorder, says the U.S. Office on Women's Health.

Stuff Mom Never Told You former host Cristen Conger said PCOS was one of the most popular health topic requests she got from fans.

Advertisement

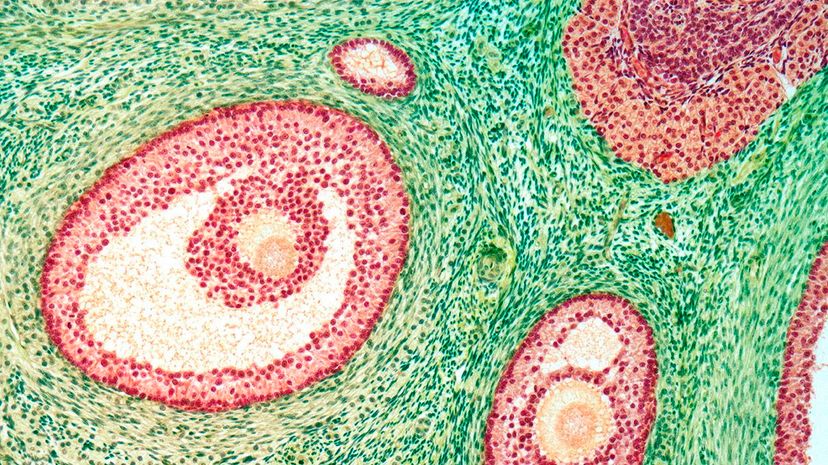

Researchers think both a hormonal imbalance, heredity and a high level of insulin may contribute to the syndrome, which has a variety of symptoms such as excess hair growth, acne and weight gain. Some PCOS symptoms, however, pose a bigger problem for long-term health. Take those irregular periods: They're pesky, sure, but they also can cause cysts in the ovaries and infertility. In fact, although PCOS is one of the most common causes of female infertility, the root cause of PCOS has eluded researchers for a long time, leaving doctors with no "cure," or umbrella treatment.

But researchers in Australia published a study in March that found a surprising origin for PCOS: the brain. Kirsty Walters specializes in the field of female reproduction and ovarian function and is an author of the study. She explains in an email that scientists typically had studied the ovaries when it came to PCOS: "The inclusion of 'ovary' in the naming of PCOS suggests that it is primarily a condition affecting, and possibly originating in, the reproductive organs." Which seems pretty obvious, right? If the condition affects the ovaries, that's the source of the problem.

And scientists had good reason to assume the ovaries were the cause.

"Androgen excess in women is the most consistent feature in women with PCOS," explains Walters. And in females, androgen — a group of hormones usually associated with males — is largely made in the ovaries. So look to the ovaries right?

Well, androgen receptors also exist in the brain. And when researchers decided to test how mice reacted to high doses of androgen to trigger PCOS, they wanted to see how different androgen receptor modifications played out. They found that, as predicted, the control group of regular mice developed PCOS with the high androgen dose. The mice without any androgen receptors didn't get PCOS. But then things got interesting: The mice with androgen receptors in their ovaries got PCOS (although at rates not as high as the control group's), but the mice without androgen receptors in the brains did not get the condition, leading scientists to believe that ovarian androgens aren't the sole origin of PCOS.

This wasn't the expected result, says Walters. "We were very surprised that our data provided evidence that this syndrome may start in the brain and not the ovaries as has long been assumed," she says.

Of course, there's a lot more research to be done before we can declare an origin story for PCOS: "The next steps are to look in more detail at the specific androgen driven pathways that are operating in the development of PCOS," Walters says, and human studies also have not been conducted.

But this is a really hopeful sign that treatment for the conditions of PCOS might someday improve, says Walters, and may even address a root cause. "The findings from this research are significant as they propose a new concept in the way in which we think about PCOS," she says. "We have identified that the brain is an important site in the development of this condition which gives us a new direction of where we should focus when we are trying to develop treatments that will target the cause of PCOS."

Advertisement