You may have read stories about babies born with a protruding liver or ropes of intestine hanging outside the abdomen. While this idea may seem far-fetched, these types of conditions occur more often than you might think. In certain forms, they occur as often as one in 5,000 births.

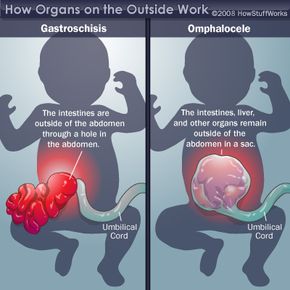

These birth defects can be life threatening, especially since they come with the risk of other defects, infection and complications. The good news is that we've learned a lot about these conditions over the past few decades. With this information, doctors have improved detection and treatment methods dramatically. Let's take a look at two conditions in which organs, or parts of organs, appear outside of the body: gastroschisis and omphalocele.

Advertisement

Both of these conditions happen when something goes awry during organ development. Between six and 10 weeks after conception, the baby's intestines, stomach and liver jut into the umbilical cord. By week 10, the baby's intestines usually go back into the abdomen. Throughout these early stages of development, there's a small opening in the baby's abdominal muscles, which the umbilical cord passes through on its way to the placenta. In later stages of development, these abdominal muscles grow together to close this tiny opening. When the abdominal organs don't return to the abdominal cavity and the muscles fail to close, this is called either gastroschisis or omphalocele, depending on the severity.

We'll look at gastroschisis -- the less severe condition -- on the next page.

Advertisement