If you were to happen upon the epicenter of drug-addled counterculture in 1969 -- the intersection of Haight and Ashbury Streets in San Francisco -- you would be more likely to believe you had found the source of mental illness instead of the cure. Among the multitudes of homeless, tie-dyed kids shuffling up and down the street with wild-eyed expressions, you might very well conclude that they'd gotten their hands on something mystical, but not necessarily something healthy.

The discovery of LSD's otherworldly effects by chemist Albert Hofmann in 1943 didn't necessarily lead him to a re-examination of everything he thought he knew about the properties of the universe, but the world's first LSD trip did lead the scientist to research the properties of the consciousness-altering drug itself.

Advertisement

However, by August 1965, Sandoz Laboratories (Hofmann's employer) had ceased production and distribution of LSD-25 due to its growing recreational use and the publicity it generated, much of it centering on recreational zaniness, "bad trips" and horrific hallucinatory experiences. Responsibility for the drug's distribution fell to the National Institute of Mental Health, creating a good deal of red tape for those wishing to do legitimate research on the drug.

While there is clearly something profoundly amazing about LSD and its effects, Western hesitancy to embrace spirituality -- drug-induced or no -- as a scientific means to an end has limited the amount of study the U.S. research establishment has committed to LSD. That, and the antics of one-time Harvard professor Timothy Leary.

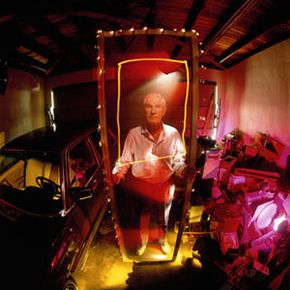

Leary's early studies of hallucinogens were vastly overshadowed by his subsequent unorthodox and somewhat criminal lifestyle, and his excesses and publicity-seeking more or less derailed academic research of hallucinogens for several decades. Leary's high-profile troubles with the law (including an escape from jail in 1970) and messianic promotion of LSD-25 to the masses guaranteed that better-behaved researchers in America's universities would suffer a loss of reputation -- and even government funding -- if they attempted to investigate the troublesome, mind-expanding substance.

Leary has left this earth (literally -- some of his ashes were sent into space after his death) but LSD has stuck around. There has been a resurgence in research into LSD effects on the brain, and even in the absence of much official study in the past few decades, there has been plenty of personal study and anecdotal evidence collected about the benefits and risks the drug might hold.

Can drugs like LSD help treat mental illness?

Advertisement