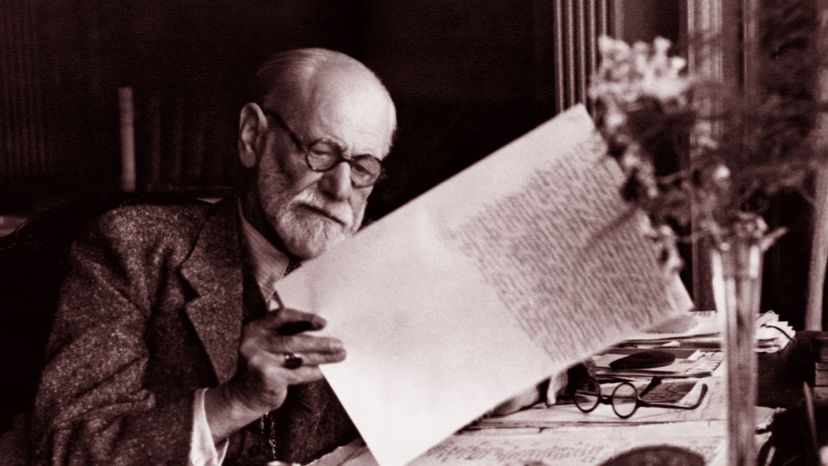

A century or so ago, Sigmund Freud was revered as the father of psychoanalysis. The legendary neurologist was also the person who came up with the theory of the id, ego and superego; the notion of penis envy; and the idea of the Oedipus Complex, among many others. But by the late 20th century many critics viewed him almost as a charlatan, as advancing science appeared to prove most of his ideas very wrong.

Nevertheless, Freud is still considered one of the most influential giants of the 20th century, mainly because he developed the notion of the unconscious mind. Prior to that, Western thought centered around positivism, the idea that knowledge comes only through reason and logic and that we can rationally control ourselves and the world. It was Freud who said positivism was wrong — that we're actually not aware of everything we're thinking and often act on thoughts that are subconscious [source: Psychologist World].

Advertisement

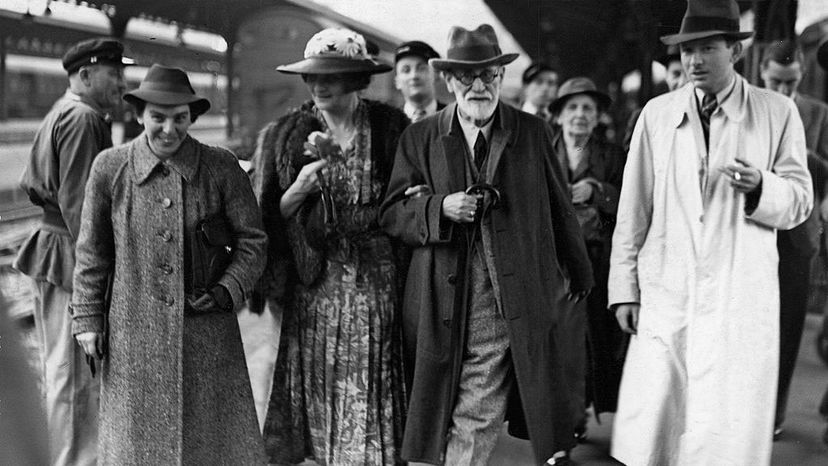

Before delving further into his work, let's look at his life. Sigmund Freud was born in Freiberg, Moravia (part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire), in 1856, to a Jewish family. The Freuds soon relocated to Vienna, and in 1873 young Freud began studying medicine at the University of Vienna. He didn't want to become a doctor, though. A science wonk, Freud's interest lay in neurophysiological research. But during that era, it was more practical to work as a physician rather than a researcher. Since Freud was engaged to a woman named Martha Bernays, practicality trumped desire. Freud decided he would specialize in neurology and then enter private practice. (Sigmund and Martha married in 1886 and had six children between 1887 and 1895.)

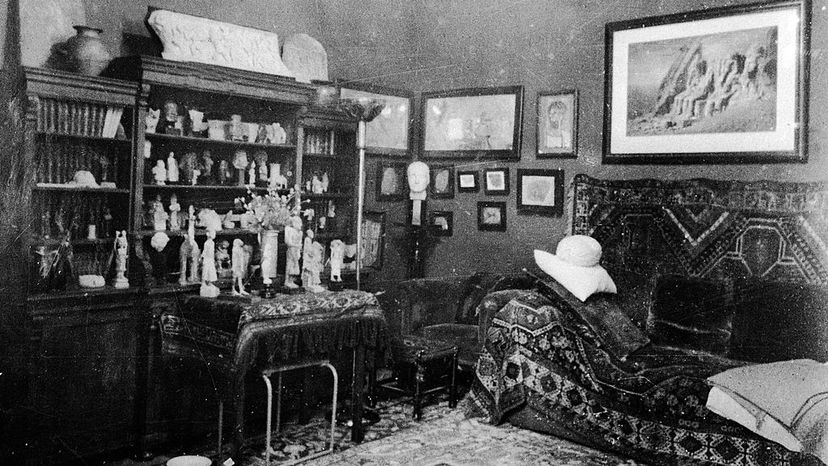

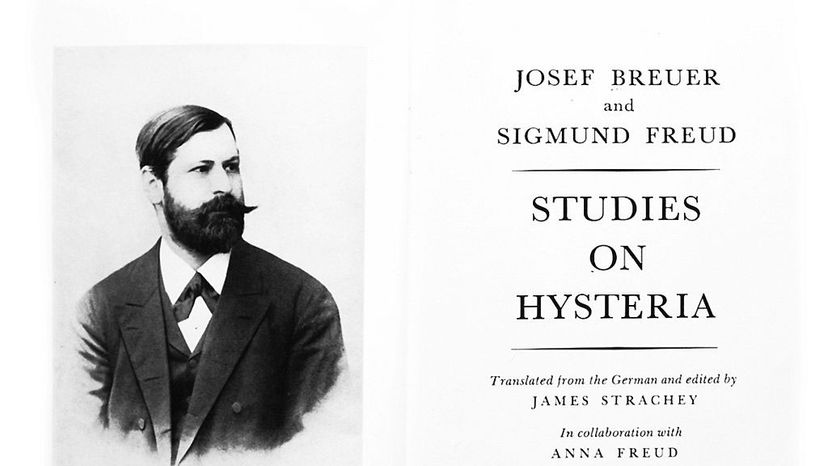

After graduation, Freud began treating hysteria with his friend Josef Breuer, a distinguished Austrian physician. Hysteria in those days was the name given to patients — usually women — who had various physical symptoms that couldn't be linked to any particular physical cause. Common ailments included paralysis, convulsions and loss of speech. Eventually, Freud opened his own practice in nervous and brain disorders [sources: BBC, McLeod].