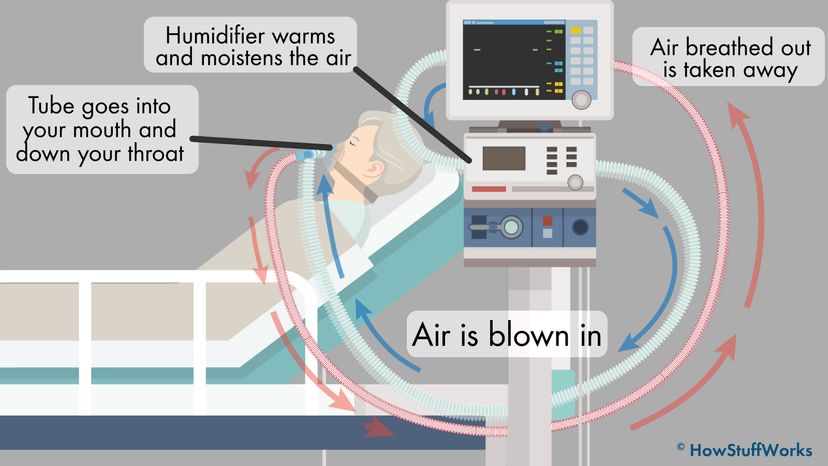

To get this all to work, hospitals depend upon the expertise of highly trained professionals called respiratory therapists. "The respiratory therapist determines the appropriate settings to match the patient's respiratory needs based on the underlying disease condition," explains Timothy R. Myers, a respiratory therapist and chief business officer of the American Association for Respiratory Care, by email. "From that point, they provide constant monitoring and assessment and modify the setting as the patient's condition improves or worsens. This would include noninvasive monitoring and measurements from blood analysis to look at oxygen and carbon dioxide levels."

This requires a lot of careful management, because lungs are pretty complicated, Myers explains. While it's useful to think of the lungs as a balloon for illustrative purposes, in reality, they're "more like a network of millions of balloons that must transfer gases between the lungs and the circulatory system. When the lungs are damaged or diseased, each lung and the millions of balloons require gas entry in and out differently than when healthy. Each patient is unique."

In recent years, there have been some advances in how ventilators are used. "Research has shown that using low breath size and low pressures improves outcomes," Currier explains. "Also, patients with severe respiratory failure may at times be turned on their stomachs while on the ventilator, a process called prone positioning, which can often improve their oxygen levels. Finally, for some patients whose oxygen levels remain low despite being on a ventilator, they may be able to receive Extra-Corporeal Membranous Oxygenation (ECMO) in some very specialized centers. This highly intensive therapy can circulate the blood outside of the body to provide additional oxygen."

Lutchen's research focuses upon developing safer mechanical ventilators. "Initially the ventilator is working to save a life by keeping proper O2 and CO2 levels," he says. "But it does this by pushing air in and exposing the lung to abnormal pressures, often larger pressures to help expand a stiffer and/or narrower lung. Also a ventilator is programmed to give the exact same breath every time where normal breathing varies a little from breath to breath and we periodically take a big breath. If you need to be on a ventilator for a very long time there is a risk of the repetitive large pressures to cause Ventilator Induced Lung Injury (VILI) which could facilitate Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). Now the ventilator may no longer be able to provide enough O2 and CO2 exchange."

That's why Lutchen is working with lead investigator Bela Suki, a professor of biomedical engineering at BU, on a concept called variable ventilation, in which the ventilator delivers variable breaths similar to a natural breathing pattern, to avoid repetitive abnormal pressures in the same location when a person breathes. "There is some evidence in animals that this approach is less likely to lead to VILI and can facilitate recovery from ARDS," Lutchen says. "But the approach has not yet been tested in humans."