Unless you've been blessed with supernaturally healthy genes (Captain America, I'm looking at you), you've probably experienced the triage process at least a couple of times. Those of us who ail, hurt and heal require medical evaluation from time to time, and a quick once-over by the triage nurse is typically part of the experience. The term triage is traced to the French word "trier," which means "to sort" [sources: Robertson-Steel]. This moniker is appropriate because sorting is exactly what's going on during triage, whether you realize it or not.

"The triage process sorts patients in a manner that ranks them by level of acuity," explains Scott Batchelor, M.D., M.P.H, a pediatric emergency medicine physician at Children's Healthcare of Atlanta at Scottish Rite. This ranking process allows hospitals to prioritize patients based on severity of illness or injury, with the intent of treating the sickest first. So if you show up in the emergency room with a broken toe or other non-life-threatening problem, you can pretty much be guaranteed to get bumped down the list by incoming patients with more pressing concerns.

Advertisement

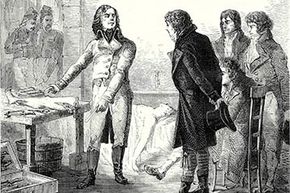

While the idea of medical triage might sound like common sense, someone had to create it. The concept was implemented in 1792 by Baron Dominique-Jean Larrey, who served as surgeon in chief to Napoleon's Imperial Guard [source: Robertson-Steel]. The advancing state of modern warfare had begun to produce great numbers of injuries and casualties, emphasizing the need for more efficient caregiving to wounded soldiers on the battlefield. Rather than forcing soldiers to wait hours or for the end of fighting for the day for treatment as they had before, doctors began evaluating injured men on the spot. Larrey's formula for sorting soldiers was based solely on severity of injuries, with the most desperately wounded placed ahead of those who could wait, albeit uncomfortably [source: Iverson and Moskop].

British naval surgeon John Wilson further evolved the process in 1846 by focusing attention first on patients who could be successfully treated, rather than spending precious time and scarce resources on mortally wounded soldiers [source: Iverson and Moskop].

During World War I, the triage formula was tweaked yet again, with the emphasis being on treating the most people one could in the shortest time. As a military surgical manual of the time put it, "A single case, even if it urgently requires attention ... may have to wait, for in that same time a dozen others, almost equally exigent, but requiring less time, might be cared for."

As you can see, there are several ways to triage patients. Next, we'll look at how modern hospitals make these decisions.

Advertisement