The majority of children reported missing each year are runaways or the objects of custody disputes. In fact, a child is much less likely to be abducted than to be in a car accident; however, media attention would lead people to believe that child abduction is quite common. Of the children that are abducted, 25 percent are taken by strangers; most abducted children are taken by someone they know.

Small children are at particular risk of being victimized. They are taught to respect adults, to be polite, not to question older people, and certainly not to yell or fight. In addition, they are easily swayed by offers of food or treats. Their small size also makes it easy for someone to physically abduct them.

When a child is reported missing, law enforcement agencies become involved. It is essential to report a missing child to law enforcement immediately. Many states have Amber Alert systems that rapidly notify the public when a child has been abducted. Cases of missing children can also be logged into the FBI's National Crime Information Center computer.

Parents' organizations are also taking a vigorous role, not only in helping to locate missing children but also in preventing abductions. The oldest group is Child Find, established in 1980. This group publishes an annual directory of missing children. Other groups provide information and educational materials to parents and lobby for stiffer penalties for offenders.

The individual family still has the major responsibility for preventing child abduction. There are a number of precautions you can take. For example, never leave an infant alone in a car, stroller, or shopping cart, even for a second. If your child is in child care, be sure the center has a strict policy regarding pick-up.

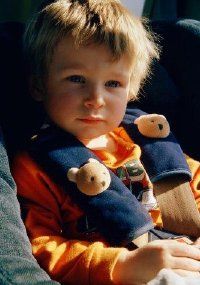

If you are in a large public area, such as a mall or the airport, consider using a child harness. While some people object to "keeping a child on a leash," harnesses ensure that your busy toddler is physically connected to you and cannot wander away or be abducted. Electronic devices that sound an alarm when a child wanders beyond a certain distance from a parent are also available.

Starting when he is three years old, you can discuss the problem directly with your child. Approach this subject simply and straightforwardly. Talk about what to do, but not about the consequences of kidnapping to avoid scaring your child needlessly. Broach the subject gradually, as different situations arise. Provide frequent gentle reminders by asking your child how he would respond to a stranger.

When instructing your child to avoid "strangers," define the word. Explain to your child that he should avoid conversation or contact with anyone who you have not met together. Be sure your child understands that no one may take him someplace without you coming along and that no one may touch him in any way that makes him feel uncomfortable. Remind your child that this includes family members, friends, neighbors, and other people he knows.

Teach your child to say "No" to anyone he does not know, who makes him feel afraid, or who wants to take him someplace. If someone your child does not know offers him candy or asks him to help find a lost puppy, he should be taught to say "No." He should ignore people who ask him for directions or beckon him closer. If they persist, he should run or yell and even fight if the person attempts to touch him.

Teach your child his name, complete address (including city and state) and phone number (including area code). Don't buy items, such as T-shirts, with your child's name on them. A stranger could use that knowledge to approach your child in a nonthreatening way. Establish a code word for emergency use in case your child needs to be picked up by someone else. Read-aloud books and videos are available to help teach your child these lessons.

You may want to keep a file with your child's fingerprints, dental records, and current photographs. The value of fingerprinting, however, is controversial. Though it helps you feel you are taking steps to protect your children, it will not prevent their disappearance. It will only help identify a small child who doesn't know his or her name or one who has recently been murdered. Some people consider fingerprinting, especially when schools or police receive copies, a violation of a child's constitutional rights to privacy and to freedom from self-incrimination. Others feel it alarms children unnecessarily. Whether to fingerprint your child must be your individual decision.

You can take many precautions, then, to protect your child when away from home, from car seats to careful driving, from fingerprinting to teaching your child to say "No." While you don't want to become excessively wary, you do need to be concerned-for your child's sake.

As more and more children use the Internet to do homework, play games, and chat with friends, it becomes more important for parents to set rules and limitations to protect their children. Although it is difficult to monitor your child's Internet use, you can demonstrate an interest in which Web sites your child visits, who he contacts, and how he uses the Internet. Talk with your child about the friends he makes on the Internet. Explain why your child must never give out any identifying information that could lead someone to find him; this includes home and school addresses, school activities, and travel plans. Do not allow your child to meet anyone from the Internet in person, either at home or anywhere else. Gently remind your child that he doesn't really know anything about the friends he meets on the Internet. Although people may send him a picture, it's possible that they are entirely different from how they present themselves to your child.

Encourage your child to engage in activities that do not involve the Internet. Your child's school and local law enforcement agencies may offer educational materials on Internet safety.

Though they rarely serious, playground accidents are the leading cause of injury to elementary school children. Read about how parental supervision increases playground safety next.

This information is solely for informational purposes. IT IS NOT INTENDED TO PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE. Neither the Editors of Consumer Guide (R), Publications International, Ltd., the author nor publisher take responsibility for any possible consequences from any treatment, procedure, exercise, dietary modification, action or application of medication which results from reading or following the information contained in this information. The publication of this information does not constitute the practice of medicine, and this information does not replace the advice of your physician or other health care provider. Before undertaking any course of treatment, the reader must seek the advice of their physician or other health care provider.