Throughout history, people have done some strange things to their skin. From the 15th century to the 19th century, for instance, pale white skin was in fashion. In order to achieve this look, many fashionable women and men would bleach their skin with a mixture of lead and vinegar to stay on top of the trend. Unsurprisingly, the practice was extremely dangerous, since pores would absorb the arsenic and, over time, slowly poison the blood and major organs. Many other cosmetics had various combinations of lead, arsenic and mercury that peeled away skin and left terrible scars [source: Mapes].

Today, we fortunately know a lot more about our skin and what it's supposed to do. Your skin is actually your body's largest organ, with a surface area of over six feet (1.8 meters). It actually makes up around 16 percent of your total body weight [source: BBC]. Skin is constantly changing, too, replenishing itself at a rate of about 30,000 to 40,000 cells a minute. This means that each year you lose and replace roughly nine pounds (4.1 kilograms) of skin [source: Kids Health].

Advertisement

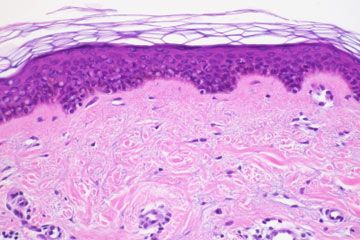

The skin is made up of three layers. The epidermis is the outermost layer, or the layer you can see and touch. The dermis is the layer below the epidermis. It's right below the epidermis, and it contains nerve endings, blood vessels, and oil and sweat glands. The dermis also holds collagen and elastic, proteins that keep skin firm and strong. Finally, there's the subcutaneous layer, which is made up mostly of fat. Each layer of your skin performs specific functions that help to cover and protect your body, regulate body temperature and provide you with a sense of touch.

Read the next page to discover more about the epidermis's role as your body's security guard.

Advertisement