If you've ever stood at a podium to address a crowd, you probably felt a few butterflies in your belly. But it probably wasn't the only thing you were feeling. Odds are little droplets of moisture began to form on your brow and the palms of your hands, too.

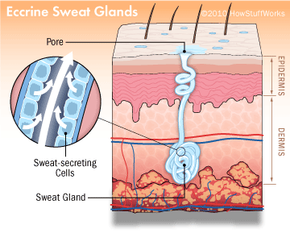

You can thank your eccrine sweat glands for your new glow. These glands cover most of your body, but are concentrated on the hands, feet and forehead. And, they're quite in-tune with your psychological state. Start feeling a little nervous and the highly sympathetic eccrine sweat glands rev into action, secreting droplets of moisture that bead on the top of your skin. The good news is this rush of perspiration isn't cause for nose-wrenching alarm. Before you reach for the nearest body spray, keep in mind this type of sweat is clear and odorless because it's comprised mostly of water (with just a pinch of salt). The smelly sweat comes from apocrine sweat glands, which we examine in another article.

Advertisement

Of course, eccrine sweat glands have another, perhaps more practical purpose: temperature regulation [source: SkinCareGuide]. Ever wonder why you sweat in the sun? The idea is that by releasing moisture, eccrine sweat glands help cool the skin and keep your core temperature from skyrocketing. But, like most internal bodily functions, eccrine sweat glands launch a rather complex process long before you ever see -- or feel -- the sweaty result. We'll explain how the process works, next.