You can't believe this is happening. In a proactive health move, you undergo a CA-125 test, which screens for ovarian cancer. The test result comes back positive. Shocked and reeling, you spend an agonizing week waiting for the results of a subsequent surgical procedure.

When the results are finally in, they're negative — you don't have ovarian cancer after all. That first result was a false positive. You're elated, yes, but also angry. What's the use of having a screening test if it might not be accurate?

Advertisement

When it comes to your health, the more informed you are, the better. Medical tests can produce one of four results:

- True positive. The test says you have condition "X" and you really do.

- True negative. The test says you do not have condition "X" and you really don't.

- False positive. The test say you have condition "X," but you really do not.

- False negative. The test says you do not have condition "X," but you really do.

While many medical tests yield very accurate results, others do not. So if you're facing a medical screening, it's important to discuss with your physician how reliable the results will be. It's also good to be aware that if your test yields a positive result, you will likely undergo a second, more accurate, test. This isn't a big problem if the second test involves, say, a noninvasive blood draw. But sometimes the subsequent test is a surgical procedure and/or is risky to perform. You don't want to undergo something like that if it isn't necessary.

Keep in mind, too, that it can be days or even weeks before the results of a second test come in, potentially leaving a healthy you and your loved ones stressed, terrified and sleep-deprived for no reason.

So how common are false positives? A study published in 2009 in the Annals of Family Medicine found a high risk for false-positive results in screening tests for prostate, lung, colorectal and ovarian cancers. And the risk went up with the number of tests administered. Results were compared after participants received four tests for various cancers versus 14:

- The cumulative risk of a false-positive result after four tests was 36.7 percent for men and 26.2 percent for women.

- The risk of a false-positive result for those who had 14 tests nearly doubled, to 60.4 percent for men and 48.8 percent for women [source: Cancer Connect].

Perhaps more alarmingly, a study published in a 2017 edition of American Family Physician found nearly 60 percent of current or former smokers who underwent a lung cancer screening via low-dose CT were given some type of positive result – but nearly 98 percent of those ended up being false positives [source: American Family Physician].

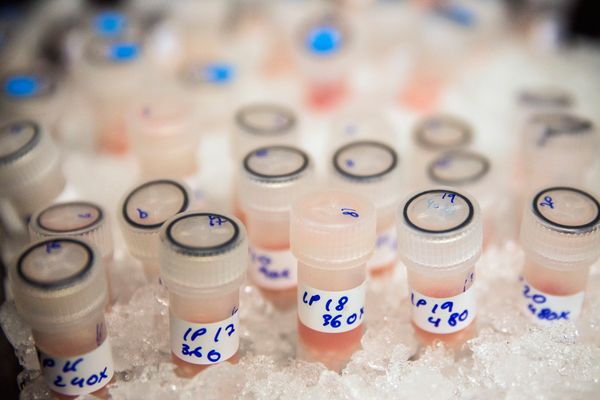

In 2020, with the rapid development of various COVID-19 tests to tackle the global coronavirus pandemic, the issue of false-positive test results became a concern. Some of the molecular tests, done via nasal or throat swabs, or by testing saliva and other bodily fluids, carry a false-negative rate of 20 percent. That may sound high, but that rate was for testing performed five days after people noticed COVID-19 symptoms. For those tested earlier, the false-negative rate skyrocketed to as much as 100 percent [source: Shmerling].

False-positive rates for COVID tests are generally rare; a March 2021 review of four rapid COVID-19 tests found that the tests correctly gave a positive COVID-19 result in 99.6 percent of patients who took it. Another review of 16 different rapid tests found that the antigen tests correctly ruled out infection in 99.5 percent of people who had symptoms and in 98.9 percent of people without symptoms.

So we can see that false negatives are a bigger problem than false positives but both exist. Part of the issue with COVID-19 test accuracy is that the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) gave the green light to the use of hundreds of diagnostic tests under its emergency use power. So there are numerous tests available, all with varying degrees of accuracy. In fact, in October 2021, an Australian maker of an at-home COVID-19 test had to recall the kits because of an unusually high rate of false positives.

Recently, the FDA began warning health care providers and others about false-positive results for COVID-19 antigen tests, which many people take because the results are quickly available. The FDA believes that false-positive results may be due to health care providers not following the test instructions, the processing of multiple specimens in one batch, insufficient cleaning of instruments or workspace and other reasons [source: FDA].

Of course, all these test inaccuracies we've discussed don't mean screening tests should be avoided, or that you shouldn't have more than a certain number. Clearly, the tests do catch a lot of diseases, which translates to lives saved. And in the case of COVID-19, you have to keep in mind that tests are being rapidly developed due to the extreme seriousness of a pandemic, and one in which the virus keeps morphing. Still, it's important to know the accuracy rate of any test you're considering, and the positives and negatives associated with any necessary follow-up tests so you can make an informed choice.

Advertisement