Children learn about taste in grade school -- out of the five senses, it seems like one of the simplest. There are no cones, rods or lenses. There are no tympanic membranes or miniscule bones. Yet scientists know less about taste than they know about sight and hearing -- senses that are far more complex. Why is something seemingly so rudimentary so complicated and controversial? Why is taste so mysterious?

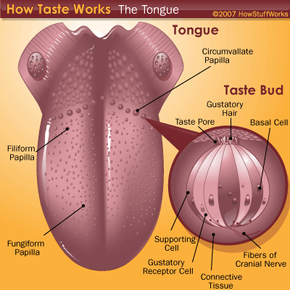

To start with, most people confuse taste with flavor. Taste is a chemical sense perceived by specialized receptor cells that make up taste buds. Flavor is a fusion of multiple senses. To perceive flavor, the brain interprets not only gustatory (taste) stimuli, but also olfactory (smell) stimuli and tactile and thermal sensations. With spicy food, the brain will even factor in pain as one aspect of flavor.

Advertisement

Testing sensation is also a subjective science -- taste perhaps more subjective that most. Some people have inherited genetic traits that make certain foods taste disgusting. Others, called supertasters, have abnormally high concentrations of taste receptors. To their heightened palates, bland food tastes perfectly flavorful. And, as we all know, food tastes differently to different people -- we don't all like the same flavors.

In recent years, scientists have expanded the definition of taste, allowing one, and possibly two, primary tastes into the original canon of four -- sour, bitter, sweet and salty. They've challenged the tongue map, the biology-class staple that charts distinct regions of taste. Food scientists have even tampered with taste receptor cells, blocking or stimulating them in an effort to cut sweeteners and salt out of food without sacrificing flavor.

In this article we'll learn about the physiology and psychology of taste.

Advertisement