One day in 17th-century England, a woman was having trouble with one of her upper canine teeth. Accordingly, she had it extracted — the go-to treatment for a bad tooth at the time. But taking out the problem tooth didn't help, and soon she noticed (brace yourself) pus coming from the hole where her tooth used to be.

This was profoundly gross, but it got worse from there.

Advertisement

Trying to find the source of the problem, the enterprising woman turned to foreign objects — a pencil and a feather — to explore where her tooth had been. Before long, she was rushing to a doctor, insisting she'd just stabbed her own brain.

Luckily for her, this particular doctor happened to know exactly what was going on. Not many 17th-century physicians were clued in to the anatomical structures that make it possible for someone to insert a long, thin object through a tooth socket and surprisingly far up into the skull. But Nathaniel Highmore was so knowledgeable about it that the anatomy in question was named for him.

In other words: Our dental patient definitely wasn't touching her brain with a feather. She'd been poking around in Highmore's Antrum, better known these days as the maxillary sinus — a mostly air-filled cavity in the skull, next to the nose. To help her understand the situation, Highmore even showed her some of his detailed anatomical drawings.

For decades, it was thought that Highmore had been the first to make precise anatomical drawings of the maxillary sinus. Then in 1901, the scientific drawings of Leonardo da Vinci were discovered, and researchers learned the great artist had rendered a highly accurate image of the sinus in question a hundred years or so before Highmore.

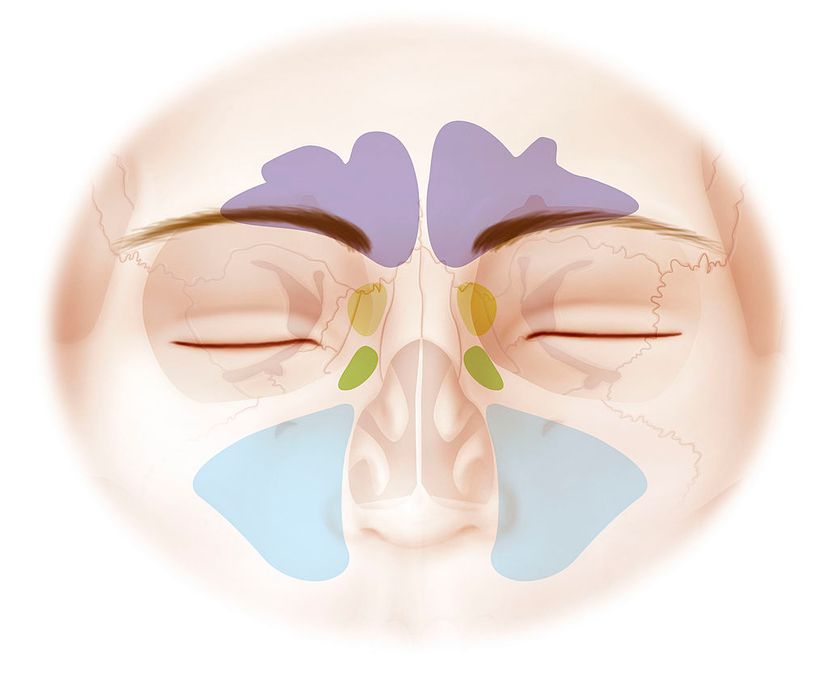

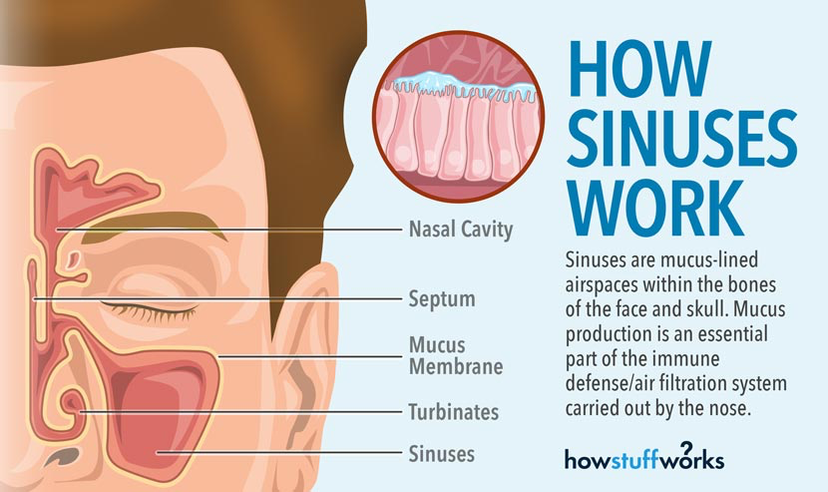

Although nobody had made such nice drawings of the sinuses before da Vinci and Highmore, people had known about them for millennia. The ancient Egyptians appear to have been aware of them thanks to their penchant for removing the brains of the dead through their noses during the mummification process. Mind you, they probably didn't use the maxillary sinus for this stunt, but rather the ethmoid one [source: Mavrodi and Paraskevas]. That's right, there's more than one kind of sinus. There are actually four major sinuses: maxillary, ethmoid, frontal and sphenoid.

So, we've got some holes in our heads, and when we are experiencing sinus-related issues, they can make our teeth hurt. Interesting. But why? What's the purpose of having a network of air-filled pockets in the human head bone?

Advertisement