Think back to the last time you went to a rock 'n' roll concert or a fireworks display. Do you remember that peculiar ringing in your ears after the show stopped? The noises around you were muffled briefly, replaced with a buzzing inside your head, almost as if your ears were screaming. In a way, they were.

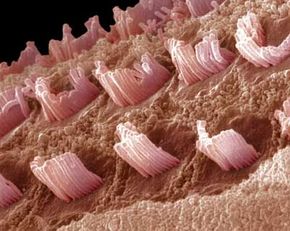

Noise levels louder than a shouting match can damage parts of our inner ears called hair cells. Hair cells act as the gatekeepers of our hearing. When sound waves hit them, they convert those vibrations into electrical currents that our auditory nerves carry to the brain. Without hair cells, there is nothing for the sound to bounce off, like trying to make your voice echo in the desert.

Advertisement

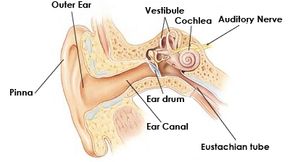

Hair cells reside in the inner ear inside the shell-shaped cochlea. Bundles of hair-like extensions, called stereocilia, rest on top of them. When sound waves travel through the ears and reach the hair cells, the vibrations deflect off the stereocilia, causing them to move according to the force and pitch of the vibration. For instance, a melodic piano tune would produce gentle movement in the stereocilia, while heavy metal would generate faster, sharper motion. This motion triggers an electrochemical current that sends the information from the sound waves through the auditory nerves to the brain.

When you hear exceptionally loud noises, your stereocilia become damaged and mistakenly keep sending sound information to the auditory nerve cells. In the case of rock concerts and fireworks displays, the ringing happens because the tips of some of your stereocilia actually have broken off. You hear those false currents in the ringing in your head, called tinnitus. However, since you can grow these small tips back in about 24 hours, the ringing is often temporary [source: Preuss].

Read on to find out exactly how something invisible like sound can harm our ears, how you can protect those precious hair cells and what happens when the ringing never stops.

Advertisement