In the 1950s, when Virginia farmer Henrietta Lacks was facing cancer, she wasn't thinking that one of her tissue samples would be used for decades to come in scientific research -- polio vaccine development, a trip to space, gene mapping and more. We know this because no one asked her permission. Her family didn't find out about it for 25 years, and only then because a researcher contacted them asking for samples of their DNA [source: Zielinski].

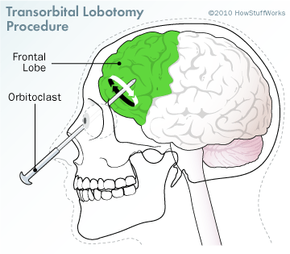

Let's also take a look at lobotomies, operations in which doctors break connections in patients' brains to treat conditions such as depression and schizophrenia. At the height of lobotomy practice in the 1940s, prior to advancements in mental health care, this ice-pick-through-the-eye-socket procedure appeared to be sound. The treatment even snagged a Nobel Prize in 1949 [source: Jansson].

Advertisement

Today, we might be shocked that these things were considered OK. But in life, there are humans behind science, and what these people consider "right" and "wrong" can change. That's the trick with ethics, the study of right and wrong. Accepted beliefs evolve. So how does ethics work in medicine, and how might it be different in 100 years?

Different professions have their own ethical standards. Examples of ethical themes in most of them include honesty, carefulness, integrity, non-discrimination and confidentiality. Because of medical ethics, you can have a reasonable expectation that your personal information will be kept private, your clinical providers won't be impaired, and your wishes for care while incapacitated will be respected.

Ethics are so highly valued in medicine that most doctors pledge to adhere to the Hippocratic Oath. This oath, developed by the Greek physician Hippocrates about 2,500 years ago, outlines principles of medical ethics. For example, it incorporates rules of honor and justice, cautions against criminal activity and maintains patient rights [source: Alper].

However, just as we have adjusted our moral compasses to view taking unauthorized samples from patients for research as wrong, medicine continues to change -- and so does medical ethics.

In 100 years, what practices that are common today will shock our descendants? For one, it's possible that the thought of drug testing on actual humans over, say, robots will be absurd. Even today, the Institute of Food Research in the United Kingdom uses a mechanical stomach for tests regarding food safety and pharmaceutical development [source: Entrepreneur].

Also -- though having a doctor perform a surgery out of his house today would make the five o'clock news -- there might come a time when surgeons aren't even in the operating room. After all, the advent of robotic surgery is already allowing surgeons to guide robots with small instruments for certain procedures, such as coronary artery bypass and gallbladder removal [source: Medline Plus]. A surgeon still seeking access to that operating room would possibly be falling short of his or her ethical obligation to continue to advance his or her skills.

These types of speculations may seem comical, but similarly, the Nobel Prize selection team from 1949 probably never would have guessed we would be debating the ethics of lobotomies today. We'll have to wait 100 years to see what happens.

Advertisement