Approximately 2,400 years ago, Hippocrates and other medical practitioners tried to make sense of a strange disorder that involved paralysis. They called the phenomenon "apoplexy," a Greek word that translates to being violently struck down, as if from a club. Not knowing much about the brain, these ancient doctors attributed the condition to a crippling blow from the gods. Not until the 17th century would it be understood that this "stroke" of paralysis was a result of bleeding and blockage in the brain.

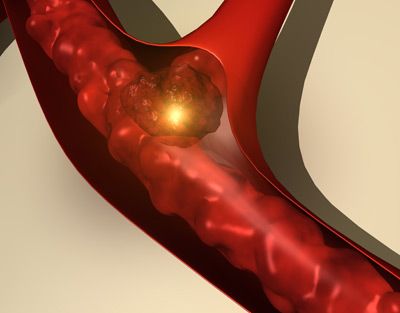

A stroke occurs when the arteries that carry blood to the brain are either blocked by a clot or when they rupture causing a hemorrhage. When the blood flow to the brain stops, the parts of the brain not getting oxygen or nutrients are almost immediately affected.

Advertisement

If there's no blood getting to the brain stem, basic life support functions including breathing and heart rate are threatened. If the clot blocks blood from reaching the cerebellum -- the center that regulates coordination and balance -- then a person might lose control of their muscles. In the cerebrum, there's plenty of damage that can be done, with lobes that process sensory information, produce speech and control motor function at risk. The two halves of the cortex are responsible for analytical and perceptive tasks, as well as movement for the opposite side of the body.

When any part of the hard-working brain is denied blood, these functions are threatened. When a stroke occurs, a person might immediately go limp on one side. The sufferer may not be able to form words or see straight. The brain is suddenly a battlefield, where supplies (blood) have been cut off and soldiers (brain cells) are dying. Time is of the essence -- brain cells may be permanently lost. That's why some neurologists prefer to call strokes "brain attacks." Just as with heart attacks, strokes should be treated with extreme urgency so that blood flow can be restored and permanent brain damage averted.

However, that doesn't always happen; strokes are the third leading cause of death in the United States, as well as the leading cause of permanent disability. About 700,000 strokes occur each year just in the United States [source: Kolata]. But these numbers may not have to be so high, and in this article we'll learn how most strokes can be prevented by controlling risk factors and how recognizing symptoms allows for earlier treatment. First, though, read the next page to learn about what's going on in the brain when a stroke occurs.

Advertisement