For the estimated 28 million Americans with hearing loss, life is a series of missed opportunities. Frustrated friends and family members often tire of shouting and will just give up on communicating altogether. This can make the world a very lonely place for the hearing-impaired. Hearing aids -- small electronic devices that amplify sound -- can help restore many of the sounds that hearing-impaired people are missing. However, research finds that very few people who need hearing aids actually use them. Only one out of every five Americans who could benefit from a hearing aid wears one, according to a 2006 study from Duke University [source: Medical News Today].

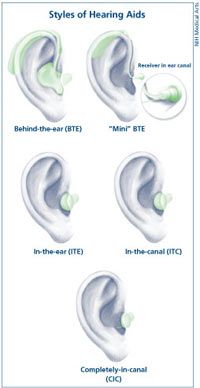

Some people pass on hearing aids because of the cost, while others do so because they are embarrassed to be seen wearing them. What they don't realize is that many hearing aids are relatively inexpensive, and many of today's hearing aid styles are so small that they are nearly impossible to spot.

Advertisement

In this article, we'll find out exactly how hearing aids work, and learn about new technologies that are providing clearer, more natural sound for people with hearing loss. But first, let's look at what causes hearing loss.

What Causes Hearing Loss?

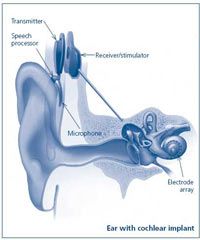

When you listen to something, whether it is a car alarm or a dog barking, the sound travels through the opening of your outer ear and causes your eardrum to vibrate. Three small bones in your middle ear carry this vibration to the cochlea -- the shell-shaped structure in your inner ear. The vibration stimulates hair cells, which create an electrical current in the auditory nerve. This current transmits the sound via nerve impulses to your brain, where it is processed into noise, like the sound of a car alarm or that of a dog barking.

People lose hearing in one of two ways:

Conductive hearing loss occurs when sound doesn't move as it should through the eardrum, ear canal or the three bones of the inner ear. It can be caused by earwax, a punctured eardrum, fluid in the ear, a genetic defect or an infection. The result is a sensation as though your ears are plugged. Conductive hearing loss can be treated with surgery.

Sensorineural hearing loss involves damage to the cochlea. It's the most common type, affecting about 90 percent of people with hearing loss. Sensorineural hearing loss can be a byproduct of aging, or it can occur due to infections, genes, head trauma, exposure to loud noises or fluid buildup in the inner ear. This is the type of hearing loss that a hearing aid can help.

Advertisement