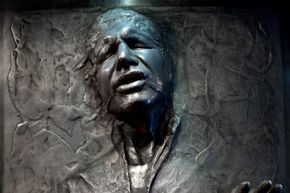

Cryotherapy seems to have begun a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away. Infamously, at the end of "The Empire Strikes Back," the nefarious bounty hunter Boba Fett manages to get Han Solo in his clutches and decides that the easiest way to transport the errant pilot back to the lair of Jabba the Hutt is to freeze him in a substance called carbonite.

As most of us pop-culturally literate folks know, in "The Return of the Jedi," Princess Leia and Luke Skywalker team up to rescue Solo. After recovering from some temporary blindness, Solo seems not only back to normal, but, if anything, possessed of his trademark wise-cracking cool and impressive flying abilities in even greater abundance than before.

Advertisement

Had Solo's remarkable recovery come about a decade earlier, it could've inspired real-life researchers to experiment with freezing as a form of therapy. Unable to acquire carbonite, they would've turned to liquid nitrogen, which, thanks to rock concert smoke machines and "Dr. Who" reruns, seems cool enough to fit the bill.

Let's say they shut themselves in a small closet and released the liquid nitrogen, which instantly turned to a sub-zero misty gas, chilling them to the bone. A few minutes would be all they needed before leaping from the ice chamber feeling frozen, charged with endorphins and ready to battle the Dark Side.

In reality, whole-body cryotherapy is said to have originated in Japan in the 1970s when Dr. Toshima Yamauchi stuck his rheumatoid arthritis patients in supercooled chambers to reduce their pain.

From there the therapy moved to Europe and eventually to North America where it's become one of the latest health fads among athletes and celebrities. But how does it work? And, more importantly, does it?

Advertisement