Among the many diseases and afflictions that we face as we age, Alzheimer's disease remains among the least understood and most frightening. This deadly disease attacks that most essential and complex of organs -- the brain -- and can leave the patient confused, depressed and helpless while challenging the ability of loved ones to cope.

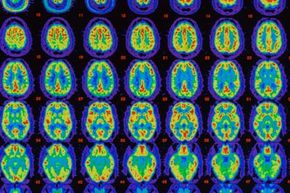

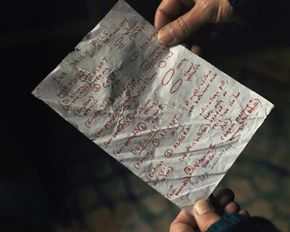

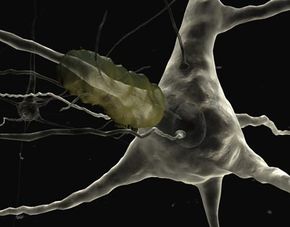

Alzheimer's disease is a neurodegenerative disease and the most prevalent form of dementia, representing up to 70 percent of all dementia cases [source: Alzheimer's Association]. It has no cure and is always fatal. Its causes are mysterious, yet we do know some things about how the disease develops and its consequences. We know that it affects a person's memory, language ability and even basic thought processes. Eventually, rudimentary actions like swallowing become impaired or impossible. Alzheimer's destroys some of the brain's 100 billion neurons and shrinks it (significant shrinkage occurs by the disease's advanced stages). Alzheimer's patients usually live for up to 10 years after diagnosis, though sometimes they live twice as long [source: NIH].

Advertisement

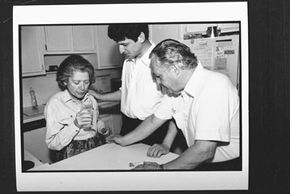

Alzheimer's disease was named after Dr. Alois Alzheimer, who in 1906 discovered unexpected changes in the brain matter of a deceased patient. The patient, known as Frau Auguste D., had shown, prior to her death, many of the now recognized symptoms of Alzheimer's disease, such as loss of memory, difficulty speaking and trouble in understanding others. When he examined her brain after her death, Dr. Alzheimer saw that Auguste's brain had shrunk and that fatty deposits had appeared among her brain cells.

Today, 4.5 million people in the United States may have Alzheimer's [source: NIH]. Five percent of Americans ages 65 to 75 have the disease [source: NIH]. The prevalence might be as high as 50 percent among those at least 85 years old [source: NIH].

While Alzheimer's is frequently associated with old age, it can develop before the traditional retirement age of 65. Early-onset Alzheimer's disease, also called younger-onset Alzheimer's disease, occurs in people as young as 30. This unusual form of the disease, which likely has a strong hereditary component, may affect hundreds of thousands of Americans.

Advertisement