Imagine yourself behind the wheel, coming up on a four-way stop. You have places you'd really like to be, so you're impatient with the rules of the road, which dictate a certain order by which drivers advance through the intersection. Yet you know that if you were to barrel through the stop sign, you'd likely cause an accident with those drivers that had the right-of-way. Cars would pile up, horns would honk and your neck might feel out of whack. Your feelings would rapidly change as you consider everything from your soon-to-rise insurance premiums to concerns for occupants of the other cars.

The brain operates in much the same way. Most of the time, neurons release ordered electrical pulses which dart around the brain delivering messages to the spinal cord, muscles and nerves. But when all the neurons start firing at once, the brain can be subject to traffic jams as well. The neurons' rapid and wild firing overwhelms the rest of the brain, causing a seizure to occur. Epilepsy is a neurological disorder characterized by recurring seizures. It's estimated that about 50 million people worldwide suffer from epilepsy, but it's still a fairly misunderstood and stigmatized condition [source: Baruchin].

Advertisement

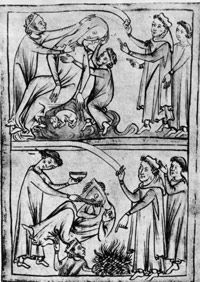

In ancient days, seizures were alternately believed to be communication with the divine or with the devil. A seizure was proof-positive that you were dealing with a witch during the 15th century. Some may picture actress Natalie Portman wearing a helmet in the 2004 film "Garden State" when they think of epilepsy. The title of the 1997 book "The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down" refers to how a family from Laos described their daughter's seizures. Others call seizures electrical storms in the brain.

But what causes these electrical storms, these traffic jams? And how does a person deal with epilepsy? We'll investigate these questions, starting with how a seizure works. Most of the time, the neurons in your brain are firing at a rate of 80 times per second; during a seizure, the neurons fire at 500 times per second [source: Judd]. Obviously something's going on in the brain, but how does that manifest itself in the body? Turn the page to find out.

Advertisement