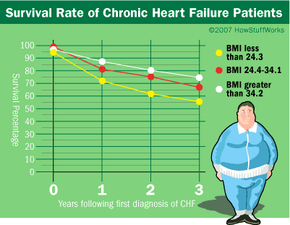

About 65 percent of Americans are either obese or overweight, and the Centers for Disease Control has classified obesity as an epidemic in the United States. According to NIDDK/NIH, obesity costs Americans more than $117 billion annually in health care [source: NIDDK/NIH]. If you are obese, you have a 50 to 100 percent increased risk of premature death than someone of normal weight. Obesity is a risk factor in other conditions, like high blood pressure, heart disease and type-2 diabetes. However, recent studies have shown that obese people with chronic diseases have a better chance of survival than normal-weight individuals do. This finding has been called the obesity paradox. But before you reach for those extra doughnuts or postpone going on that diet, let's examine obesity.

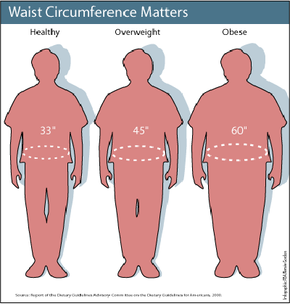

Obese people have excess body fat. Overweight people have excess body weight (weight includes bone, fat, and muscle). Generally, women have more body fat than men do. Women with more than 30 percent body fat and men with more than 25 percent body fat would be considered obese.

Advertisement

Scientists can measure body fat with X-ray absorption techniques and underwater weighing, which are based on the fact that fat tissue has a different density than bone or muscle. But these methods aren't practical for routine doctor's visits. So, primary health care providers use other methods (like height, weight and skin-fold thickness).

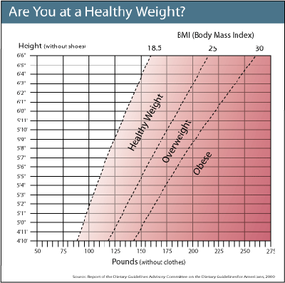

The most popular and convenient method for estimating obesity is the body mass index (BMI). BMI is a ratio of weight to height. This is the formula:

BMI = weight (lb) / [height (in)]2 x 703 (English measurements)

BMI = weight (kg) / [height (m)]2 (metric measurements)

For example, a 5-foot-5-inch, 150-pound woman would have a BMI of 25. According to these BMI categories, she is overweight but not obese.

- Less than 18.5 = underweight

- 18.5 to 24.9 = normal weight

- 25 to 29.9 = overweight

- More than 30 = obese

There are several online charts based on BMI calculations that you can use to categorize your weight.

Obesity affects men and women of all racial and ethnic backgrounds, but women have a higher percentage of obesity than men. In the United States, African-Americans have the highest percentage of obesity, followed by Mexican-Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Obesity affects about 11 to 28 percent of children, who show the same racial and ethnic obesity patterns. Obesity increases the risk for hypertension (high blood pressure), cardiovascular disease, stroke, cancer, gallbladder disease and diabetes. Obese patients can have higher levels of cholesterol and lipids circulating in their bloodstreams. This can lead to the buildup of atherosclerotic plaques in blood vessels, which increases the risks of high blood pressure, heart attack and stroke. So, obesity is a well-known risk factor for developing cardiovascular disease.

Next, we'll learn how scientists discovered the obesity paradox.

Advertisement